|

In January 1843, the Conservative government under Sir Robert Peel established a Commission of Enquiry to study the Scottish system of poor relief. There had been growing concerns about the effectiveness of poor relief in Scotland, which at the time was in the hands of the Kirk Sessions of the Church of Scotland. A few months after the Commission was set up, the Church of Scotland split in the Disruption, with around 40% of ministers leaving to form the Free Church. This further eroded the position of the Church of Scotland, and made substantive reform inevitable. The earliest record of poor law in Scotland dates back to 1425 (not 1424 as is sometimes incorrectly stated). Those aged between 14 and 70 who were able to earn a living themselves were forbidden from begging, on pain of branding for a first offence and execution for a second offence: Of thygaris nocht to be thollyt Three years later, the king decreed that officials who failed to implement this act would be fined. In 1535, the system was further formalised. Poor relief was only to be granted to individuals in their parish of birth, and the “headmen” of each parish were to award tokens to eligible paupers, thereby introducing the concept of a licensed beggar. People caught begging outside of their parish of birth were subject to the same harsh penalties as before. An Act for punishment of the strong and idle beggars and relief of the poor and impotent was passed in 1579. This established the basic system of poor relief which was to continue for hundreds of years. Sic as makis thame selffis fuilis and ar bairdis or utheris siclike rynnaris about, being apprehendit, salbe put in the kingis waird and yrnis salang as they have ony guidis of thair awin to leif on If they had no means of sustenance, their ears were to be nailed to the tron or any other tree, and they were then to be banished. The penalty for repeat offenders was death. As for able-bodied beggars: all personis being abone the aige of xiiij and within the aige of lxx yeiris that heirefter ar declarit and sett furth be this act and ordour to be vagabundis, strang and ydle beggaris, quhilkis salhappyne at ony tyme heirefter, efter the first day of Januar nixtocum, to be takin wandering and misordering thame selffis contrarie to the effect and meaning of thir presentis salbe apprehendit; and upoun thair apprehensioun be brocht befoir the provest and baillies within burgh, and in every parochyne to landwart befoir him that salbe constitutit justice be the kingis commissioun or be the lordis of regalities within the samyne to this effect, and be thame to be committit in waird in the commoun presoun, stokkis or irnis within thair jurisdictioun, thair to be keipit unlettin to libertie or upoun band or souirtie quhill thai be put to the knawlege of ane assyse, quhilk salbe done within sex dayis thairefter. And gif they happyne to be convict, to be adjuget to be scurget and brunt throw the ear with ane hett yrne So “strong and idle” beggars were to be captured, imprisoned or put in stocks or irons, and brought before a court within 6 days. Upon conviction, they were to be burnt through the ear with a hot iron. The law puts in this caveat: exceptit sum honest and responsall man will, of his charitie, be contentit then presentlie to act him self befoir the juge to tak and keip the offendour in his service for ane haill yeir nixt following, undir the pane of xx libris to the use of the puyr of the toun or parochyne, and to bring the offendour to the heid court of the jurisdictioun at the yeiris end, or then gude pruif of his death, the clerk taking for the said act xij d. onlie. And gif the offendour depart and leif the service within the yeir aganis his will that ressavis him in service, then being apprehendit, he salbe of new presentit to the juge and be him commandit to be scurgit and brunt throw the ear as is befoirsaid; quhilk punishment, being anys ressavit, he sall not suffer the lyk agane for the space of lx dayis thairefter, bot gif at the end of the saidis lx dayis he be found to be fallin agane in his ydill and vagabund trade of lyf, then, being apprehendit of new, he salbe adjuget and suffer the panes of deid as a theif. In other words, the convicted idle beggar would be spared this punishment if someone offered him a job for a year. If he were to leave such employment without his master’s approval, he would be burned through the ear, but if convicted a second time, he would be put to death as a thief. The law then moves on to detail who should be subject to punishment. Not just beggars, per se, but also: all ydle personis ganging about in ony cuntrie of this realme using subtill, crafty and unlauchfull playis, as juglarie fast and lowis, and sic utheris, the idle people calling thame selffis Egyptianis, or ony utheris that fenyeis thame selffis to have knawlege of prophecie, charmeing or utheris abusit sciences, quhairby they persuaid the people that they can tell thair weardis deathis and fortunes and sic uther fantasticall imaginationes So people claiming to use witchcraft, self-styled “Egyptians” (i.e. Gypsies or Romanies), those claiming to have the gift of prophecy, charms, or fotune-telling. Other people to be punished include those with no visible means of support, minstrels, singers and storytellers not officially approved, labourers who have left their masters, those carrying forged begging licences, those claiming to be itinerant scholars, and those claiming to have been shipwrecked without affidavits: utheris nouthir having land nor maister, nor useing ony lauchfull merchandice, craft or occupatioun quhairby they may wyn thair leavingis, and can gif na rekning how they lauchfullie get thair leving, and all menstrallis, sangstaris and tailtellaris not avowit in speciall service be sum of the lordis of parliament or greit barronis or be the heid burrowis and cieties for thair commoun menstralis, all commoun lauboraris, being personis able in body, leving ydillie and fleing laubour, all counterfaittaris of licences to beg, or useing the same knawing thame to be counterfaittit, all vagabund scolaris of the universities of Sanctandrois, Glasgw and Abirdene not licencit be the rectour and deane of facultie of the universitie to ask almous, all schipmene and marinaris allegeing thame selffis to be schipbrokin, without they have sufficient testimoniallis Those hindering the implementation of the law would be subject to the same penalties. Having established the penalties, the Act requires all poor people to return to their parish of birth or habitual residence within 40 days of this act. Parishes were to be responsible for supporting their native-born paupers or those who had been habitually resident there for seven years, and were to draw up rolls of the poor. Aged paupers could be put to work, and punished if they refused. Children of beggars aged between 5 and 14 could be taken into service until the age of 24 for boys or 18 for girls, and could be punished if they absconded. An Act of 1597 on “Strang beggaris, vagaboundis and Egiptians” explicitly transferred responsibility for poor relief to Kirk Sessions. The 1649 Act anent the poore introduced a stent or assessment on the heritors of each parish to pay for poor relief. The 1672 Act for establishing correction-houses for idle beggars and vagabonds ordered the opening of correction-houses for receaving and intertaining of the beggars, vagabonds and idle persones within their burghs, and such as shall be sent to them out of the shires and bounds aftir specified in Edinburgh, Haddington, Duns, Jedburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Glasgow, Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, Ayr, Dumbarton, Rothesay, Paisley, Stirling, Culross, Perth, Montrose, Aberdeen, Inverness, Elgin, Inveraray, St Andrews, Cupar, Kirkcaldy, Dunfermline, Banff, Dundee, Dornoch, Wick and Kirkwall. By the time the Commission of Enquiry was set up, it was clear that provision was inadequate. The Commission’s exhaustive report (nearly 6000 pages in total, including evidence; even the index is 300 pages long!) made a series of recommendations:

in every such Parish as aforesaid in which the Funds requisite for the Relief of the Poor shall be provided without Assessment the Parochial Board shall consist of the Persons who, if this Act had not been passed, would have been entitled to administer the Laws for the Relief of the Poor in such Parish; and in every such Parish as aforesaid in which it shall have been resolved, as herein-after provided, to raise the Funds requisite for the Relief of the Poor by Assessment, the Parochial Board shall consist of the Owners of Lands and Heritages of the yearly Value of Twenty Pounds and upwards, and of the Provost and Bailies of any Royal Burgh, if any, in such Parish, and of the Kirk Session of such Parish, and of such Number of elected Members, to be elected in manner after mentioned, as shall be fixed by the Board of Supervision This meant that where a mandatory assessment was used to raise funds for poor relief, the Kirk Session no longer controlled the system, although it was still entitled to appoint up to six members of the Parochial Board. When the Act entered into force, 230 of 880 parishes were subject to statutory assessment. Within a year, that almost doubled to 448 (compared to 432 using voluntary contributions). By 1853, 680 parishes were using statutory assessments, compared to just 202 relying on voluntary contributions. The number of parishes relying on voluntary contributions continued to decline steadily, with only 108 doing so in 1865, and just 51 by 1890.

For genealogists, the implications are clear: after 1845, records of the poor will mostly be found among local government records, mostly held in local council archives around the country. That said, there are significant post-1845 poor records found among the Kirk Session records, not least because as we have seen, in many cases responsibility for poor relief remained with Kirk Sessions long after the Poor Law was enacted. However, the records of the Board of Supervision, being a national body, are held at the National Records of Scotland. One of the responsibilities of the Board of Supervision was to hear appeals against inadequate relief. These appeals are an excellent source for family history – they will tell you much about the individuals, as well as their families. They often include medical reports, information on the earnings of applicants and their families, names and details of children and the like. Before 1845, records of poor relief are more often with Kirk Session records. We saw in a previous post how it was possible to trace individual paupers in for instance Kirk Session accounts and other church records. Some of these records can provide excellent detail - we've seen examples of church poor relief records giving names, relationships, occupations, details of payment in kind, poor children being lodged out with other families and so on. They can be therefore be an excellent source for family historians, and should not be neglected. We are currently working on a national index to a particular set of Poor Law records from 1845 to 1894, which we plan to release later this year.

1 Comment

Two days ago, I wrote about death (in the guise of mortcloths), and yesterday's blog was about newspapers. So I thought I'd continue with a morbid approach to blogging by writing about obituaries. Obituaries have a long tradition, and most newspapers have at the very least carried what is often jocularly referred to as Hatches, matches and dispatches (Births, marriages and deaths).

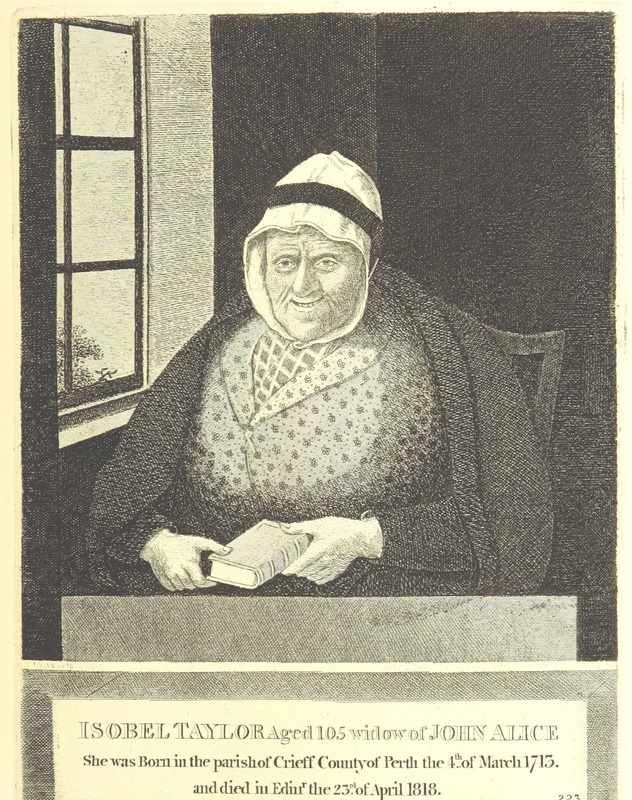

In historic Scottish newspapers, these notices are usually fairly brief, and generally only mention the great and the good - either national figures, or prominent local figures. Ordinary people usually didn't get a look in. One instance in which ordinary people would be mentioned was if they lived to a ripe old age. Even today, centenarians are relatively uncommon, but in the 19th century, they were sufficiently rare as to be reported in newspapers often far removed from where they lived. Our first centenarian is Isobel Taylor or Alice/Ellis, whose death was reported in 1818: Died in Old Assembly Close on 23d ult, Mrs Isobel Taylor, aged 105. She was born in the parish of Crieff, county of Perth, on the 4th of March 1713, in the reign of Queen Anne. Her memory remained nearly unimpaired, and she would converse on the events of 100 years since, with surprising correctness. Her hearing and sight were good to the last day of her life, and her recollection continued till within an hour of her death.

Old Widow Ellis was a well-known figure in Edinburgh, sufficiently so that the celebrated caricaturist John Kay (about whom we've written before) produced a caricature of her:

Old Widow Ellis

Our next centenarian, Thomas Adamson, was a weaver from Pittenweem. Unsurprisingly, his death was reported in the Fife newspapers:

Pittenweem. Longevity. Thomas Adamson, weaver in Pittenweem, died on Saturday week at the advanced age of one hundred years, five months, and two days; having been born on the 1st of May 1746. Throughout the whole course of his lengthened pilgrimage, Thomas was never peculiarly distinguished as an instrument by whom the simple denizens of earth were excited to wonder or admiration. In the literary world, he was only characterised by the “noiseless tenor of his way”. In the commercial world, by means of his industrial apparatus, he made as much noise as any other wabster of the last century. In the political world, he was merely a silent observer of the election hubbubs, for which his burgh was so eminently distinguished in days of yore, having never been invested with the franchise, either under the old or new system. In the religious department of society, he created considerable stir and noise, having for many long years occupied the precentor’s desk in the Old Kirk, where he conducted the sacred music, and gave the people line upon line according to the fashion of the good old time. In this he always aided the devotion of the sincere, and sometimes supplied fuel to the fire of waggery that through all ages has been found smouldering even in the kirk itself. Through all the vissicitudes [sic] of the commercial horizon to which this nation has been subjected, Thomas managed to rear a numerous family, and keep himself beyond the pale of starvation by tossing the shuttle, harmonising the kirk, and polishing the cheeks and chins of his fellow mortals who could not perform that duty for themselves. Being a member of a respectable society in Pittenweem, called the Trades’ Box, he in his latter years derived much benefit from the funds thereof, when the infirmities of age began to cramp his energies. We are not aware, now that Thomas has departed from the stage of time, that he has left his equal in age on this coast.

His death was also reported further afield in Dundee:

Death of Thomas Adamson, the patriarch of Pittenweem - This event took place on Saturday morning last, October 3, at ten o'clock. He was born on the 1st of May, 1746, and on the 1st of May last, had completed the extraordinary long life of one hundred years. Mr Adamson was a weaver, and continued to ply the shuttle until within a very few years back. He was what most long livers are, an early riser; six o'clock scarcely ever found him in bed; he was generally up and at work by five. He had a strong clear voice, and was for many years precentor in the parish church. He had a perfect recollection of seeing Paul Jones sail past Pittenweem, on his way to Leith, about 70 years ago, and of the tempest which providentially arose and drove the pirate out of the Firth. He never was what may be called really sick, and never complained of a head-ache. For the last six months he was confined to bed, but felt no pain or sickness. He retained his senses to nearly the last day of his life, and during harvest he was every day inquiring about how far the different farmers had got in their crops. The failure in the potato crop gave him much uneasiness. During the whole of his long life, he was only three weeks absent from Pittenweem. His fortune was not chequered with ups and downs; he always continued to plod away at work. Perhaps the most remarkable event in his whole life was the meeting which was held in the Town Hall on the 1st of May last, in commemoration of his having on that day completed his hundredth year. His body was laid in Pittenweem Church-yard on Wednesday last, and the attendance at his funeral was numerous and respectable.

The Dundee obituary adds a few more details, such as his recollection of seeing John Paul Jones and his flotilla in the Firth of Forth (this would have been in August 1779), and the fact that he'd only spent three weeks out of Pittenweem in his entire life. This obituary - possibly reprinted from one of the other Fife papers - was reproduced more or less verbatim in M F Conolly's Supplement to his Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Men of Fife some twenty years later.

Our third centenarian was the daughter of a soldier, apparently born in Edinburgh Castle. Her death was reported in Dumfries, where she'd lived most of her life: At Maxwelltown, on the night of Sabbath last, Catherine M’Donald or Hutchison, at the extraordinary age of one hundred and four years. She was born in the castle of Edinburgh early in the ’45, a year memorable for the last attempt of the Stuart family to regain the throne which they had so long tilled. Her father, a private soldier, was stationed in the garrison at the time, and being ordered to repair to Dumfries, brought his daughter along with him. Soon after her father obtained his discharge, and with his wife and child settled in the Brig-end, and thus became one of the early colonists of the now thriving burgh of Maxwelltown. Here Catherine, best known as Mattie Hutchison, resided as girl, wife, and widow, for a hundred and three years, during which she lived under seven British Sovereigns. Through her long life she conducted herself with propriety, and showed great respect for the ordinances of religion. She was somewhat eccentric in her manners, and her dress to the last was of the primitive cut, fashionable eighty or ninety years ago. She was a little deaf, but with this exception, retained the full use of her faculties up till the day of her death. She was a widow for thirty years, and had one son, who died a few years before her. Latterly she was partly dependent for her support upon parish aid, but the path of life’s decline was smoothed by the benevolence of several charitable ladies, who were very attentive to the grateful centenarian.

Once again, her age was considered sufficiently newsworthy to be reported further afield, this time in Dundee:

Death of a centenarian - On Sunday night last, Catherine M'Donald or Hutchison, residing in Corbelly Hill, Maxwelltown, departed this life, in the one hundred and fourth year of her age. She was born in Edinburgh Castle in the early part of 1745, when her father, a private soldier, was stationed with his regiment. Part of the force was ordered to Dumfries at the time of its occupation by Prince Charles Stuart in the ill-fated rebellion of the '45. Catherine, then a child at the breast, was brought by her parents to this town, and her father, having obtained his discharge, settled at the Brig-end, in which, now become the burgh of Maxwelltown, she has resided, girl and woman, for fully one hundred and three years. She wore her dress in the same fashion which prevailed when she was a young woman, and indeed, in all things was a thorough Conservative. With the exception of a slight deafness she preserved her faculties unclouded to the very last. Dumfries Herald.

Catherine appears to have had two children with her husband William Hutchison - Martha baptised 8 August 1784, and Thomas baptised 2 July 1787, both in Troqueer parish. The first obituary suggested she had been at least partly dependent on support from the parish. A quick look at the 1841 census for Troqueer shows Catherine living at Corberry Hill aged 100, where she is described as a pauper.

Records of some of the payments from the parish that Catherine received are recorded in the Troqueer Kirk Session Accounts (NRS Reference CH2/1036/20):

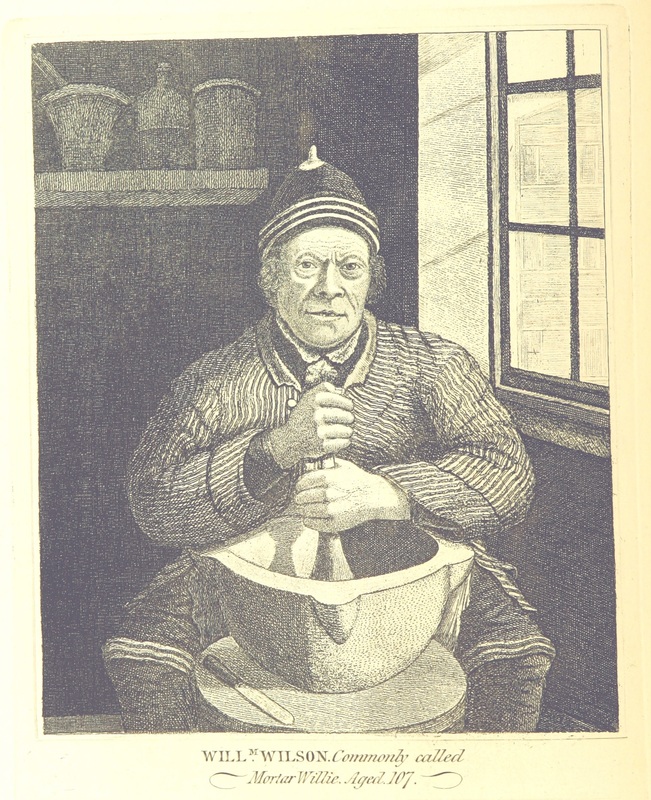

Our final centenarian was evidently another local character in Edinburgh. His death was recorded in the Caledonian Mercury:

On the 16th current, in the Old Fleshmarket Close, Canongate, William Wilson, commonly called Mortar Willie, at the advanced age of 106 years. He was taken from the plough in the rebellion of 1745, to serve in the Royal army, where he remained for several years. After being on the Continent he came home to this country, where he has since been employed in the capacity of druggist-man, 40 years of that time in this town. He has left an infirm old widow, aged 73, to whom he has been married 50 years, in very poor circumstances.

Mortar Willie's death was widely reported - in the Scots Magazine, in The Examiner, printed in London, and even in the Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser on August 10. He was also described in Kay's Portraits:

William Wilson, or Mortar Willie Strictly speaking, there is a difference between genealogy and family history. Genealogy is the study of ancestry, of biological relationships. Family history on the other hand is about people, and their stories. One of the best sources for family history stories is historical newspapers. The first newspaper is generally considered to be the Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien produced in Strasbourg in 1605. It was another 55 years before the appearance of the first Scottish newspaper, the Mercurius Caledonius, although it only ran for 12 issues before closing in 1661. Newspaper production really took off in Scotland in the 18th century with the first appearance of the Edinburgh Courant in February 1705. Newspapers have continued in Scotland since then. The oldest daily newspaper in Scotland still in print is the Press and Journal, originally published as a weekly newspaper under the name of the Aberdeen Journal in 1748. The name is perhaps slightly misleading, as it always covered national and international news, albeit with a strong local element. While newspapers may sometimes be useful for genealogy, they are often much more useful for family history. In the Aberdeen Journal of 21 July 1800 is the following short, but horrific, story: We hear from Buchan, that on Sunday the 29th ult. Margaret Keith, in Auchtydonald, was barbarously murdered. She was seen that morning with a man to whom she was supposed with child, who decoyed her to the river Ugie, and threw her in. she was scrambling to the other side, when the villain went across by a small bridge a little higher up, and ere she could reach the brink, he knocked her on the head by repeated blows of a bludgeon, when she sunk and perished. The murderer immediately absconded. The next issue of the Journal contained the following, to modern readers rather bizarre, poem, entitled "On the melancholy death of Margaret Keith, a widow in Auchtydonald in the parish of Longside, who was barbarously murdered on Sunday, 29th June, 1800" O’er scenes of woe, where common griefs prevail Newspapers not infrequently published poems from their readers, although this particular example is longer and a little more morbid than most. But as well as news, newspapers carried adverts to cover their costs. The next issue of the Aberdeen Journal carried the following: A Reward Offered Clearly the advert had the desired effect, because 4 weeks later, we can read the following: Aberdeen Three weeks later, the Journal reports - disappointingly briefly - on the trial before the Circuit Court Aberdeen The next issue is even more sparing with regards to the verdict: Aberdeen The same issue also includes an appeal for the three orphan children of the victim, Margaret Keith. It having been suggested, that a small fund should be established for the future support of the THREE ORPHAN CHILDREN of the late Margaret Keith, in Auchtydonald, who was recently found murdered in the Water of Ugie – the smallest sum, for this purpose, will be thankfully received at Mr Ewen’s, Castlestreet. We have some more details of the case, courtesy of James Bruce in his Black Kalendar of Aberdeen published in 1840: James Carle Of course not all newspaper stories will be so dramatic, or tragic. The same issue of the Aberdeen Journal that carried the long reader's poem about this terrible murder, also contained the following snippet: Marriage – At Fintray the 21st cur. Ann Ferguson, after a courtship of ten days, presented herself before the Altar of Hymen, and gave her hand to Robert Porter. The age of this venerable and happy pair amounts to about 150 years. So large was the company who honoured them with their presence, that it was judged expedient for the clergyman to perform the ceremony in the Grand Temple of Nature. That the scene of festivity might not be too soon interrupted by Sunday, the marriage was solemnized on Monday afternoon. In the evening there was an elegant ball, attended by many Ladies of the first rank in that corner of the country. From one family were present no fewer than 30 persons. An assembly so numerous, so chearful, and so elegant, has not been remembered at Fintray for 50 years past.

As a genealogist I've long identified with Haley Joel Osment's famous line in the film The Sixth Sense: "I see dead people". To non-genealogists, family historians can sometimes seem obsessed with death. Death comes to us all, in the end, and ultimately much of genealogy involves not seeing but researching dead people. Friends and family have come to accept that I can't pass a graveyard without wanting to pop in for a quick - or not so quick - look around.

Of course, most of our ancestors are dead, and as genealogists we want to know when they met their end. In Scotland there has been a legal requirement since 1855 to register all deaths, and statutory registers of death are excellent sources for family historians. In most cases, they record the name of the deceased, their spouse(s) if any, their parents, the cause of death and so on. Before 1855, however, the records are less helpful. There are gravestones, tangible reminders of the existence of our ancestors. Many graveyards have been recorded by enthusiasts and their inscriptions published (usually referred to as Monumental Inscriptions or MIs). More recently, the rise of digital photography has made collections of photographs of gravestones popular. But not everybody could afford a gravestone, and not all gravestones survive in a legible condition. A few years ago, Scotland's People made available the burials recorded in the Old Parish Registers (OPRs). These are a great resource, but they are far from complete. There are some OPR burials for around two-thirds of Church of Scotland parishes, but in some cases there are very few burials recorded - there are only two for Fearn in Angus, and only nine for Galston in Ayr. So if there is no gravestone, and no OPR burial, does that mean we can't find out when our ancestor died? Not necessarily. There is another type of record that can help: mortcloth accounts. A mortcloth (from the Latin mors meaning death) was a ceremonial cloth draped over a coffin (or a corpse if the family could not afford a coffin) at a funeral. Most families didn't have their own mortcloths - not unreasonable when you consider that any one person only needs it once! - instead hiring them for the occasion. In burghs, the individual trades might have their own mortcloths which were lent to members for the occasion. But in most cases, mortcloths were available to hire from the Kirk Sessions. In many cases, the Kirk Sessions owned more than one mortcloth - smaller ones for children, or more elaborate ones for a higher fee. (Even in death, not everyone was equal.) The money raised from renting out the mortcloth was generally used for poor relief, and as a result, the Sessions often kept good records of payments received. While they may not necessarily contain a great amount of detail, mortcloth accounts may be the only way to identify when an ancestor died. (See for instance Aberlady accounts 1826-1846, Forgandenny minutes 1783-1836 and Dalmeny Accounts 1736-1779.) They should however be treated with a degree of caution, as the date recorded for payment may be some time after the death and funeral. We've extracted some entries from Dalmeny [NRS Reference CH2/86/8 p. 294-295] below.

A couple of months ago, while doing some eighteenth-century research for a client in the Carrington Kirk Session records, I came across a much later letter which had evidently been bound in with the accounts at a later date:

[Blind-stamped address]

In a different hand – seemingly that of William Granville Core, minister of Carrington, who at this time was also acting as session clerk for the parish – the following two entries are extracted:

1695 Febry 10 Received from James Dewar in Capilaw & his wife being th[ei]r collection for the building of Kinkell harbour 7 shillings by reason they were not here the day if was gathered.

This is an example of what is known in genealogy circles as a lookup – a request for somebody to inspect a particular record set and to report back any entries that match the requester’s requirements. Instances are scattered throughout the Kirk Session records. There was a particular flurry of them following the enactment of the Old Age Pensions Act 1908, which for the first time granted the right to a pension to people aged 70 and over. Claimants had to prove their age, and often this would involve the pensions committee contacting the parish of birth to request confirmation of the information provided by applicants. Diligent clerks in some parishes incorporated copies of these lookup requests into the original Kirk Session records, sometimes providing useful information about what happened to parishioners.

Occasionally you will come across a request from someone researching their ancestry. We also recently found a letter to the session clerk of Dumbarton requesting a lookup about the writer’s grandfather, who was born in 1854. The letter was sent from Tasmania in 1973 – a fantastic discovery if you happen to be researching Robert Brown Ballantyne. In the modern age, however, you don’t have to find the name and address of the parish clerk, send off a speculative letter and wait for a response by post, which might never come. (It would seem Robert Brown Ballantyne’s grand-daughter may never have received a reply, as her international reply coupon is included with her letter in the Dumbarton records!). We have recently launched a service offering lookups in Kirk Session records for a very affordable price, which we are gradually rolling out across the whole of Scotland. Those parishes currently available are shown below. If you don’t see the parish you’re interested in listed, let us know and we’ll have a look for you.

The Church of Scotland is a Presbyterian church. Although the term Presbyterian is now often associated with a stern, austere form of Christianity, strictly speaking the term refers to the Church's hierarchical organisational structure. The supreme body of the Church of Scotland is the General Assembly, which meets annually in Edinburgh. The next level down from the General Assembly are the Synods, which are organised on a territorial basis. Synods are further subdivided into Presbyteries (whence the word Presbyterian). Finally, presbyteries are in turn divided into parishes. The parish is the basic unit of church governance.

Each parish had its own governing body, known as the Kirk Session. Each Kirk Session was convened by a Moderator, who in practice was the parish minister. The Session also had a Session Clerk who, in addition to his (until relatively recently, all members of the Kirk Sessions were men) duties as minute taker and record keeper, also had a significant role as an intermediary between the minister and the congregation. Parish schoolmasters often served as Session Clerks to supplement their meagre teaching incomes. The other members of the Kirk Session were the elders, generally chosen by the congregation. Elders were ordained for life, or until they resigned their position (usually through ill health, but occasionally elders were effectively forced out by scandal). Perhaps the best way to understand the role of Kirk Sessions is to consider them as a combination of court and management body. In some parishes – particularly larger urban parishes – the administrative functions of the Session were hived off to a separate management committee, responsible for such matters as maintaining the church buildings, secular business and the like. Before 1845, and to some extent afterwards, Kirk Sessions were also responsible for provision of support to local paupers – often including members of other denominations – and Kirk Session records contain a great deal of information about payments to poor people. These records can be particularly informative where a dispute arose as to which parish was responsible for supporting paupers. Parishes would often make interim payments to poor people, and then claim the money back from the responsible parish. We will consider Sessions' role in poor relief in a future post. But perhaps the most useful role of the Kirk Session was its quasi-judicial role. Kirk Sessions were notoriously inquisitive about what were considered sexual improprieties – particularly children born outwith marriage – and records of their interrogations of unmarried mothers are among the most interesting and useful of the Kirk Session records (see for instance here, here and here). Even if your ancestors were not cited to compear before the Session for sexual misdemeanours, they may have been cited as witnesses, or for other “scandals”, such as Sabbath breaking and irregular marriage. Other records produced by the Kirk Session include Communion Rolls (see here for an example from Kinclaven), accounts (which can include payments for mortcloth hire, which can serve as a substitute where no burial or death registers survive), testificates (the system used when parishioners moved from one parish to another, certifying that they were members of the Church), registers of marriages and baptisms (which continued after the introduction of civil registration of births and marriages in 1855, and as we have seen, can sometimes contain important information not included in the statutory registers), as well as many other records. Kirk Session records are a fantastic resource for genealogists and family historians. Unfortunately, unlike birth, marriage and death records, they have for the most part not been indexed, and are therefore much harder to access, particularly if you don’t live in Scotland. That is why we have started offering a lookup service, to make them accessible to Scottish genealogists around the world. To see which records we are currently able to lookup, browse our parish pages starting here. If we haven’t yet listed the available records for your parish, let us know and we will be glad to do so.

There have long been links between Scotland and Jamaica. As early as 1656, 1200 prisoners of war were deported to Jamaica by Oliver Cromwell. Later, many Scots migrated to Jamaica in search of their fortune. Famously, Robert Burns was set to sail for Jamaica before the success of the Kilmarnock Edition of his Poems Chiefly in a Scottish Dialect persuaded him to remain in Scotland.

Many Scots became plantation owners and wealthy merchants in Jamaica, frequently based on the exploitation of slaves. Often they would return to Scotland, having made their fortune. Others would leave money to the poor in their home parishes. One such was William Duffes (or Duffus), from Deskford in Banffshire. The Kirk Session records of Deskford include a list of the recipients of £15 left to the poor of the parish: List of the Poor of the Parish of Deskford nominated by the Revd Walter Chalmers Minister of Deskford & George Duffes in Knappycawset in terms of the will to receive the Legacy bequeathed by the late Mr William Duffes of Jamaica 17th November 1826

You can find more information on the records of Deskford - including nearly 700 heads of families from 1834 to 1840 - here.

Historically, illegitimacy – being born outwith marriage – often carried a great social stigma. It was considered something to be ashamed of – as if somehow the child was responsible for the actions of his or her parents. In my own family, my paternal grandmother was born before her parents were married, a fact that she kept hidden from my dad. She’d even gone to the length of consistently lying about her age to cover her tracks. It wasn't until about ten years after she died that I discovered the truth – much to the amusement of my dad, who had endured years of his mum putting his dad down because his father was illegitimate! This social stigma was incorporated in law: the Registration (Scotland) Act 1854 [Link] required that all illegitimate births be marked as such in the original register (a requirement which wasn’t removed until 1919). Section 35 of the Registration (Scotland) Act stated: In the Case of an illegitimate Child it shall not be lawful for the Registrar to enter the Name of any Person as the Father of such Child, unless at the joint Request of the Mother and of the Person acknowledging himself to be the Father of such Child, and who shall in such Case sign the Register as Informant along with the Mother Consequently, unless the father acknowledged paternity and agreed in person to be registered as the father, it was illegal to record his name in the birth register, with one proviso: Provided always, that when the Paternity of any illegitimate Child has been found by Decree of any competent Court, the Clerk of Court shall, within Ten Days after the Date of such Decree, send by Post to the Registrar of the Parish in which the Father is or was last domiciled, or in which the Birth shall have been registered, Notice of the Import of such Decree in the Form of the Schedule (F.) to this Act annexed, or to the like Effect, under a Penalty not exceeding Forty Shillings in case of Failure; and on Receipt of such Notice the Registrar shall add to the Entry of the Birth of such Child in the Register the Name of the Father and the Word "Illegitimate," and shall make upon the Margin of the Register opposite to such Entry a Note of such Decree and of the Import thereof In other words, the father’s name could be added to a birth record after initial registration if paternity was proven subject to a court order, although the stigma of the word illegitimate would remain. Section 36 of the Registration (Scotland) Act also illustrates an unusual feature of Scots law which distinguishes it from English law: In the event of any Child, registered as illegitimate, being legitimated per subsequens matrimonium, the Registrar of the Parish in which the Birth of such illegitimate Child was registered shall, upon Production of an Extract of the Entry of such Marriage in the Register of Marriages, note on the Margin of the Register opposite to the Entry of the Birth the Legitimation of such Child per subsequens matrimonium, and the Date of the Registration of such Marriage Under Scots law, a child born outwith marriage could be legitimated after birth per subsequens matrimonium – literally “by subsequent marriage” – if the parents later married, provided that they were free to marry at the time of the child’s birth. From a genealogy perspective, the main import of illegitimacy is that it can prove a significant obstacle to tracing the child’s paternal ancestry. However, it need not always prove to be a brick wall. Take the case of George Kerr Waterston, an illegitimate child born on October 9 1863 in Dunnichen, Angus. His statutory birth record does not name his father, instead just giving his mother’s name as Elspeth Waterston. As mentioned earlier, the law stated that in cases of illegitimate children, the father’s name could only be included if the father signed the register in person. The following entries from the records of Dunnichen parish demonstrate that the strict rules in force for civil registration did not apply to the Church, and thus how Kirk Session records can often be used to identify fathers of illegitimate children. At Dunnichen the 18th day of October 1863 years A couple of weeks later, in the Baptismal Register for Dunnichen, we find the following entry: Kerr, George Kerr Waterston (illegitimate), S[on]. [Father] John Kerr Junior, Greenhillock Tulloes; [Mother] Elspeth Waterston, Letham. Birth 9th October 1863, Baptism 9th December 1863 This entry provides another useful lesson - it's always worth checking baptismal registers, even after the introduction of civil registration.

On 31 May 1834, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, meeting in Edinburgh, enacted the Overtures and Interim Acts on the Calling of Ministers. This was the latest instalment in a long-running dispute within the Church about who should appoint the minister when a parish fell vacant. The right of patronage – the right of patrons, usually nobles or major landowners, to appoint ministers – had been controversial since the Reformation. An Act of the Scottish Parliament in 1690 vested patronage in the heritors and elders of each parish. They were given the right to propose a candidate, with the whole congregation then given the right to accept or reject the proposal.

In 1711, the British Parliament passed the Church Patronage (Scotland) Act, which restored the rights of the original patrons. The Church was strongly opposed to this, and made an annual protest to Parliament every year until 1784. Two factions emerged, the Moderates, who reluctantly accepted the Patronage Act, and the Evangelicals, who opposed it in principle. In 1730, the General Assembly passed an Act removing the right of objectors to have their objections officially recorded. The Evangelicals viewed this as an attempt to silence them. Two years later, the General Assembly granted the right of patronage to heritors and elders where a patron failed to nominate a candidate within six months. Some in the Church – notably Ebenezer Erskine – wanted this right to be transferred to the Heads of Families within a congregation. But the fact that objections could no longer even be recorded led to a schism in the Church, known as the Original Secession. A hundred years later, in 1834, the General Assembly passed the Overtures and Interim Acts on the Calling of Ministers, more commonly known as the Veto Act. The Veto Act was a victory for the Evangelical party, preventing a patron from presenting a minister if a majority of the heads of households objected to the candidate. This led to a series of court actions by patrons, and eventually led to the Veto Act being declared ultra vires in the House of Lords. For many this was the final straw, and the main consequence of the annulment of the Veto Act was the Great Disruption of 1843, with about 40% of ministers walking out of the Church of Scotland, founding the Free Church of Scotland and leaving the Church of Scotland as a minority church. Aside from the consequences for genealogy research of the Disruption itself – less than half of Scots were now members of the Church of Scotland, so researchers often have to look elsewhere than the Old Parish Registers to find their ancestors – the Veto Act is also relevant for family historians. The Act required all parishes to draw up rolls of "male heads of families, being members of the congregation, and in full communion with the Church" within two months, and to insert these rolls into the Kirk Session records. While not all of these rolls of heads of families survive, hundreds of them do, and they provide a very useful record of inhabitants all over Scotland in the years before the first nominal census of 1841. We have transcribed them (more than 150,000 names), and made them available on our website free of charge. The table below gives a complete list of them, with links to the individual parishes.

It might seem slightly incongruous to be writing about geography in a family history blog, but it's definitely not. Family history - as opposed to genealogy in the narrow sense - is really about people and place. To understand how your family lived, you have to understand the places they knew. Equally, even simply to research your genealogy, you have to have some understanding of geography, if only because most historical records were and are organised on a geographic basis.

Historically, Scotland - like England - was divided into counties. These counties were established in medieval times, and remained the main subdivision of government in Scotland until the reorganisation of local government in 1975. Churches were also organised geographically - in the case of the Church of Scotland, the basic unit was the parish. Parishes were grouped into Presbyteries, which in turn were grouped into Synods. The significance of this is that most historical records of interest to genealogists and family historians were organised territorially. So in order to find and trace your ancestors, you need to understand geography. For family history research, it's usually best to think in terms of the pre-1975 counties, of which there were 32:

Below county level, things get a little more complicated. Most genealogists tend to think in terms of parishes, and indeed that's how we've structured our website. After 1855 - when statutory registration of births, marriages and deaths was introduced in Scotland - many records are organised by registration district. These registration districts often initially coincided with pre-1855 parishes, but over the years, the differences increased, with the result that modern registration districts often bear little similarity to the original parishes. Nevertheless, parishes remain a very useful way of thinking about places.

The table below lists the Church of Scotland parishes in existence in 1854, the county in which they were located, and the year of the earliest entry in the Old Parish Registers.

|

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed