|

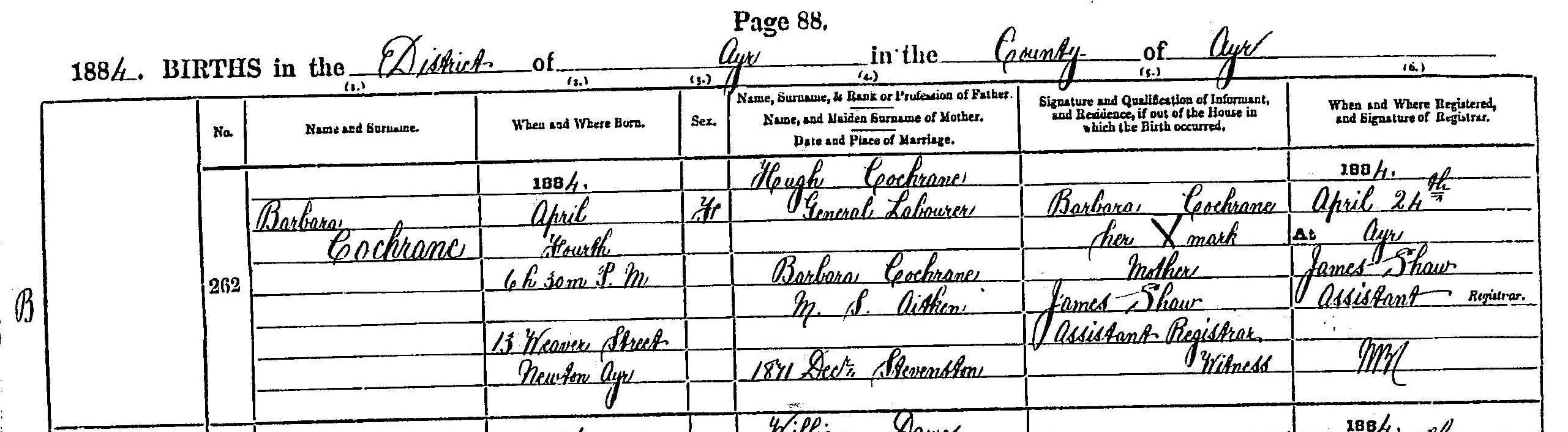

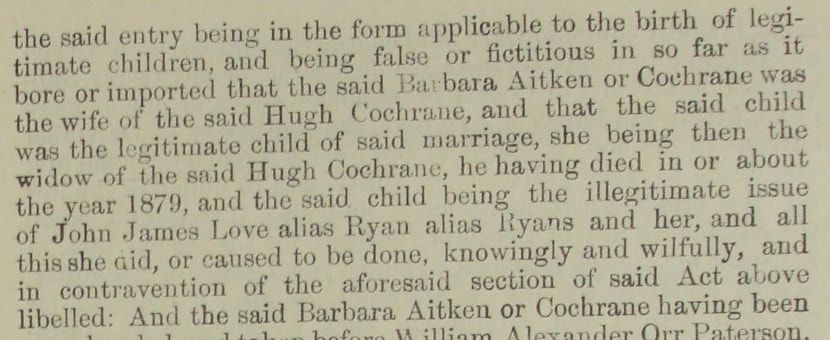

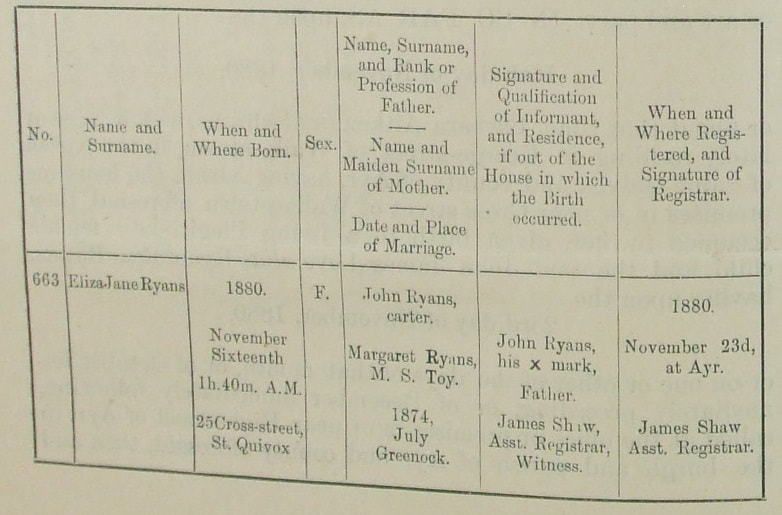

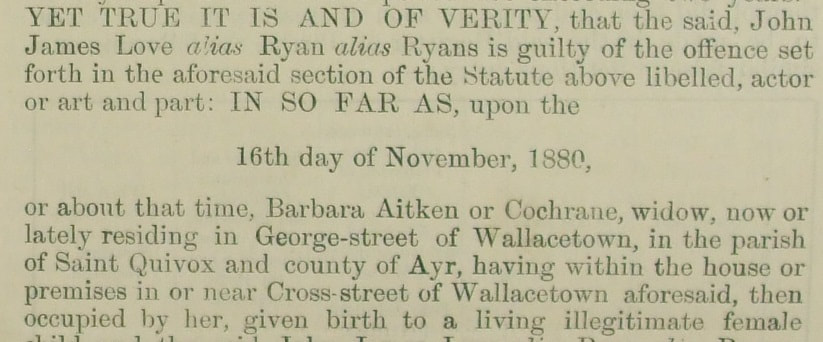

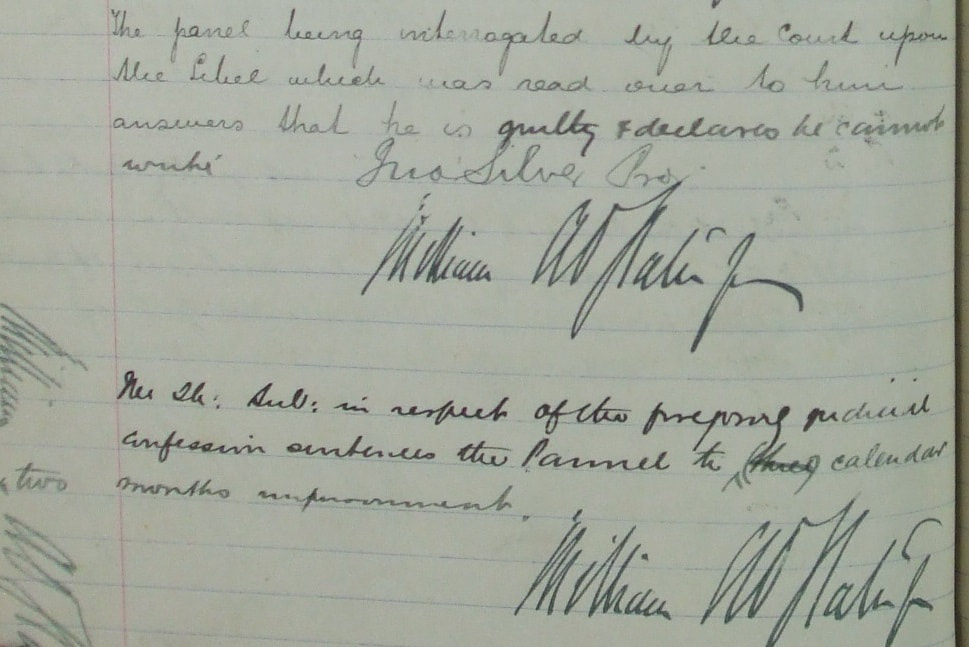

Genealogy is very much about sources – finding them, understanding them, citing them. Not all sources are equal though: a family story, passed down the generations, is still a source, just not necessarily a reliable one. Statutory registers of births, deaths and marriages on the other hand are usually much more reliable, although the accuracy of the information they contain is still dependent on the knowledge of the informant. This is particularly a problem with death registers, as the person providing the information is by definition not the subject of the information, and may not know the correct information. Scotland is unusual, in that it has a system allowing information recorded in statutory registers to be corrected after the event has been registered. This is the Register of Corrected Entries (RCE). One of the most common types of RCE entry is found when a single mother obtains a court order against the father of her child. In such cases, the court (usually a Sheriff Court) issued what was known as a Schedule (F) notification, instructing the registrar to insert in the RCE an entry recording the court’s decree and adding the name of the father to the official record. In theory, there is no time bar on adding to the RCE – the most extreme example we’ve encountered in our research was a birth record being amended more than 60 years later to record a change of name. Statutory registration was introduced in Scotland under the Registration Act of 1854. The government took the accuracy of information contained in statutory registers very seriously. Section 60 of the Registration Act reads: Every Person who shall knowingly and wilfully make or cause to be made, for the Purpose of being inserted in any Register of Birth, Death, or Marriage, any false or fictitious Entry, or any false Statement regarding the Name of any Person mentioned in the Register, or touching all or any of the Particulars by this Act required to be registered, shall be deemed guilty of an Offence, and on Conviction shall be punishable by Transportation for a Period not exceeding Seven Years, or by Imprisonment for a Period not exceeding Two Years. Despite the risk of a prison sentence, people did sometimes continue to lie – about their age, about their family background – and those lies are made official by the act of registration, and might never be corrected in the registers. Fast forward three and a half years, and on 24 April 1884, James Shaw registered the birth of a baby girl, Barbara Cochrane, born on 4 April 1884 at 13 Weaver Street, Newton on Ayr. The informant was the child’s mother, Barbara Cochrane, who informed James Shaw that the child’s father was her husband, Hugh Cochrane, a general labourer. The original register entry gives no indication that anything is amiss. However, on 8 December the following year, the Sheriff Court at Ayr issued a criminal libel against Barbara Aitken or Cochrane, accusing her of contravening Section 60 of the Registration Act, alleging that she had visited the registry office in Ayr and she “knowingly and wilfully” made, or caused to be made “false statements … in order that the said statements … might be entered … in the register of births for the said district of Ayr”. The libel then includes a facsimile of the entry in the Register of Births, and explains how the statements were false: When Barbara appeared in court on 8 December, she pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to one month in prison. Six weeks earlier, on the 27 October, John James Love alias Ryan alias Ryans appeared in court on similar charges. John’s case related to a different child though, one Eliza Jane Ryans: The criminal libel issued by the Sheriff Court, alleged that Eliza Jane was the daughter not of Margaret Toy, but of Barbara Aitken or Cochrane: John pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to two months in prison. Perhaps surprisingly, neither birth record has an associated RCE entry, resulting in a situation where an official record which operates a correction system continues to this day to contain information that the authorities knew to be false. All of this serves as a cautionary tale: genealogists should always treat every source – even those normally considered to be the most authoritative and reliable – with reasonable scepticism - don't always believe what you read. Sources:

2 Comments

I was researching in the records of Old Machar Kirk Session today when I came across the following snippet: 29 January 1838 Jane - unmarried - had confessed to having a child, and had named John Gauld as the father. That wasn't the end of the matter though. After recording several other disciplinary cases, the minute for that sederunt continued: John Gauld, mentioned above, became so turbulent that the Kirk Session found it necessary to send one of their officers for the town Officer of Old Aberdeen, their other officer being left to prevent Gauld from entering the Session House. He at last succeeded in burssting into the Session and used very threatening language and gestures to the Moderator and members present. He was requested to withdraw, but would not and furiously attacked the Kirk Officer, who was directed to put him out. At lenth George Charles, Town Officer of Old Aberdeen, came, to whom the Kirk Session gave him in charge with directions to go to the Procurator Fiscal and give him information of the outrage. It required the utmost exertion of both the Kirk Officers and the Town Officer to carry John Gauld out of the Church. Five weeks later, the Kirk Session granted Jane Ross a certificate of poverty, allowing her to take John Gauld to court for alimony. I didn't have time to continue searching the minutes to find out if John was ever summoned back to the session to account for his behaviour, but this performance was certainly not the best way to create a good impression. Source: Old Machar Kirk Session minutes (NRS Ref: CH2/1020/17) We've recently launched a "no-win no-fee" service to help you identify the fathers of illegitimate children. If you have one in your tree (and most people do eventually), why not ask us to find the father for you? If we can't name the father, you don't pay!

Historically, illegitimacy – being born outwith marriage – often carried a great social stigma. It was considered something to be ashamed of – as if somehow the child was responsible for the actions of his or her parents. In my own family, my paternal grandmother was born before her parents were married, a fact that she kept hidden from my dad. She’d even gone to the length of consistently lying about her age to cover her tracks. It wasn't until about ten years after she died that I discovered the truth – much to the amusement of my dad, who had endured years of his mum putting his dad down because his father was illegitimate! This social stigma was incorporated in law: the Registration (Scotland) Act 1854 [Link] required that all illegitimate births be marked as such in the original register (a requirement which wasn’t removed until 1919). Section 35 of the Registration (Scotland) Act stated: In the Case of an illegitimate Child it shall not be lawful for the Registrar to enter the Name of any Person as the Father of such Child, unless at the joint Request of the Mother and of the Person acknowledging himself to be the Father of such Child, and who shall in such Case sign the Register as Informant along with the Mother Consequently, unless the father acknowledged paternity and agreed in person to be registered as the father, it was illegal to record his name in the birth register, with one proviso: Provided always, that when the Paternity of any illegitimate Child has been found by Decree of any competent Court, the Clerk of Court shall, within Ten Days after the Date of such Decree, send by Post to the Registrar of the Parish in which the Father is or was last domiciled, or in which the Birth shall have been registered, Notice of the Import of such Decree in the Form of the Schedule (F.) to this Act annexed, or to the like Effect, under a Penalty not exceeding Forty Shillings in case of Failure; and on Receipt of such Notice the Registrar shall add to the Entry of the Birth of such Child in the Register the Name of the Father and the Word "Illegitimate," and shall make upon the Margin of the Register opposite to such Entry a Note of such Decree and of the Import thereof In other words, the father’s name could be added to a birth record after initial registration if paternity was proven subject to a court order, although the stigma of the word illegitimate would remain. Section 36 of the Registration (Scotland) Act also illustrates an unusual feature of Scots law which distinguishes it from English law: In the event of any Child, registered as illegitimate, being legitimated per subsequens matrimonium, the Registrar of the Parish in which the Birth of such illegitimate Child was registered shall, upon Production of an Extract of the Entry of such Marriage in the Register of Marriages, note on the Margin of the Register opposite to the Entry of the Birth the Legitimation of such Child per subsequens matrimonium, and the Date of the Registration of such Marriage Under Scots law, a child born outwith marriage could be legitimated after birth per subsequens matrimonium – literally “by subsequent marriage” – if the parents later married, provided that they were free to marry at the time of the child’s birth. From a genealogy perspective, the main import of illegitimacy is that it can prove a significant obstacle to tracing the child’s paternal ancestry. However, it need not always prove to be a brick wall. Take the case of George Kerr Waterston, an illegitimate child born on October 9 1863 in Dunnichen, Angus. His statutory birth record does not name his father, instead just giving his mother’s name as Elspeth Waterston. As mentioned earlier, the law stated that in cases of illegitimate children, the father’s name could only be included if the father signed the register in person. The following entries from the records of Dunnichen parish demonstrate that the strict rules in force for civil registration did not apply to the Church, and thus how Kirk Session records can often be used to identify fathers of illegitimate children. At Dunnichen the 18th day of October 1863 years A couple of weeks later, in the Baptismal Register for Dunnichen, we find the following entry: Kerr, George Kerr Waterston (illegitimate), S[on]. [Father] John Kerr Junior, Greenhillock Tulloes; [Mother] Elspeth Waterston, Letham. Birth 9th October 1863, Baptism 9th December 1863 This entry provides another useful lesson - it's always worth checking baptismal registers, even after the introduction of civil registration.

|

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed