|

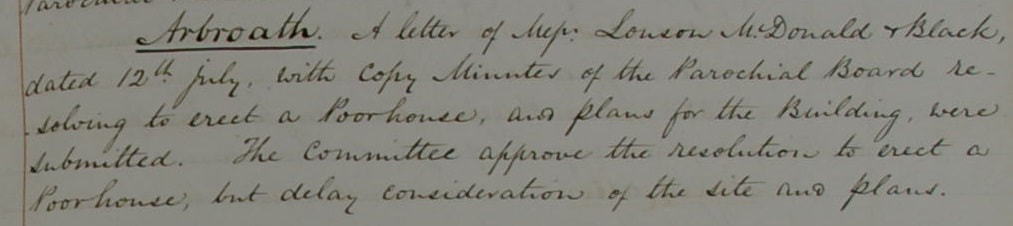

In 1855, Arbroath Parochial Board was considering building a poorhouse: 19th July 1855 The Board of Supervision, a national organisation based in Edinburgh, was responsible for overseeing implementation of the Poor Law Act of 1845. One of its statutory duties was to consider and approve plans for poorhouses. The Board evidently suggested some alterations to the plans: 24th October 1855 Eight days later, the Board met again, and signed off on the plans: 1st November 1855 The subject then seems to be dropped, for the Board of Supervision minutes do not seem to mention Arbroath's proposed poorhouse for quite some time. More than eight years later, though, Alexander Brown and six fellow Arbroath ratepayers write to the Board of Supervision with a complaint that seems a familiar one 150 years later: 10th December 1863 This rebuke from the Board of Supervision seems to have prompted the Parochial Board finally to push on with their plans to build a poorhouse, this time as a Combination Poorhouse in conjunction with St Vigeans parish: 8th September 1864 A week later, after receiving further correspondence from the builders, together with a map of the site, the Board approved of the site: 15th September 1864 Even that was not the end of the matter. It was another five months before the plans were finally approved by the Board, nearly ten years after the initial plans were submitted by the Parochial Board: 9th February 1865 Shortly thereafter, the Arbroath Combination Poorhouse finally opened, some ten years after the plans were first submitted. Sources:

0 Comments

This week we've been looking at a wide range of poor law records in preparation for the launch of a new project (coming soon: watch this space). The records of the Board of Supervision - which among other things was responsible for oversight of the operation of the poor relief system in Scotland following the Poor Law Act of 1845 - make for fascinating reading. There are obvious parallels with modern welfare systems, and the tensions inherent in them. The Board's Sixth Annual Report, published in 1851, includes a report on the Easter Ross Combination Poorhouse, which had been opened the previous year. Written in a dry, slightly bureaucratic style, it describes the progress of what was the first poorhouse in the Highlands: The Easter Ross poorhouse was erected by nine contiguous parishes. The house was opened on the 1st of October 1850, and the first pauper was admitted on the 11th of that month. I visited the house on Monday and Tuesday, the 4th and 5th of August, and communicated with the inspectors of Tain, Tarbat, Fearn, Logie Easter, Kilmuir Easter, and Rosskeen. Since 11th October 1850 to 5th August, forty-eight paupers had been admitted to the poorhouse, some of them having in the course of that time, left the house, of their own accord, and been again admitted. Five of the forty-eight paupers died at the ages of 70, 50, 71, 20 and 72 years. The immediate causes of the deaths of four were bronchitis, hydrothorax, dysentery, chorea, or St Vitus’s dance. In the fifth case, the cause of death was not entered in the record, the pauper having only very recently died. Three of the forty-eight paupers had been removed elsewhere – one of them to a lunatic asylum – four had left the house of their own accord, and had not applied for re-admission: thus at the date of my visit, there were only thirty-six paupers in the house, leaving accommodation vacant for upwards of 120. The appearance of the inmates was good, and the cleanliness maintained throughout the establishment unexceptionable. The governor appears to be well suited for the office, and keeps all his books with great neatness and regularity. The objectionable points of the management are:

The complaint that inmates are often free to come and go as they please suggests that the reporter, Mr Peterkin, was of the view that paupers should be kept out of sight. Another obvious concern - a common theme today for welfare systems - is the cost. Peterkin continues: During the first two quarters of the operation of the poorhouse, the parochial board of Rosskeen issued sixty orders for admission to paupers on the roll; of that number, only ten availed themselves of the order – all the others refused to enter the house, and were consequently struck off the roll. Seven of them were, however, subsequently admitted to outdoor relief, but four at smaller allowances than they formerly had. All the others, forty-three, have supported themselves since without parochial assistance. It appears, too, that adding the out-door allowances, which (if there had been no poorhouse), would have been payable to the paupers who took advantage of the orders of admission, to the allowances of the paupers who have supported themselves without parochial relief, for two quarters and a half, a sum would be given equal to £59 19s. whereas, the exxpense of the paupers in the poorhouse, for maintenance and general expenses for three quarters, amounted to only £58 8s 1 1/4d. Thus Rosskeen has afforded relief to their paupers, under a poorhouse system, for three quarters of a year, for a less sum than that which would have been required to give outdoor relief for two quarters and a half, supposing no poorhouse had existed. This also shows that refusal of a place in the poorhouse could lead to all poor relief payments being withdrawn. The fact that many people chose to do so suggests that the poorhouse was viewed as a last resort by desperate people. The Board of Supervision handled appeals from people claiming the relief offered them was inadequate. Many of these appeals were rejected on the basis that the applicant had been offered a place in the poorhouse. Peterkin's closing remarks also have contemporary counterparts, in the notion that those on benefits have it easy compared to the working population: Another subject was frequently touched upon by those with whom I conversed on the matter of poorhouses, namely the diet of the inmates – in regard to which, a rather general misapprehension seems to prevail, many conceiving that the diet in a poorhouse would be of such a superior description to that of the people of the country where the poorhouse would be situated that a desire would be created among the paupers of participating in it, although they might have serious objections to the confinement and discipline of the poorhouse itself. Should poorhouses ever spring up in the Western Highlands, the dietary of the Easter Ross house, which is appended, might be adopted by them, except perhaps barley-broth and pea soup, neither of which, so far as I know, are articles of food in general use among the people of the Western Highlands and Islands. Potatoes, herring, oatmeal, and mil would seem to be the requisites of a diet-table for a poorhouse there. So what was the menu provided for inmates of the Easter Ross Poorhouse? Residents were grouped into three classes: aged and infirm; adults; and children. Class 1: Aged and infirm persons

Class 2: Adult persons

Class 3: Children

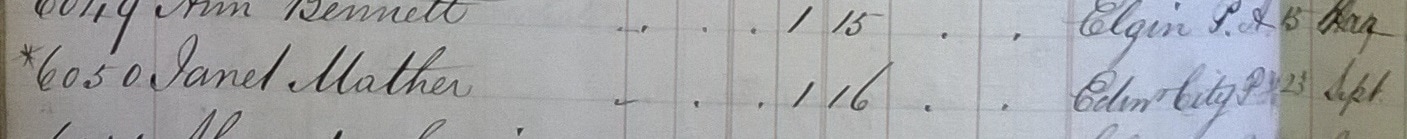

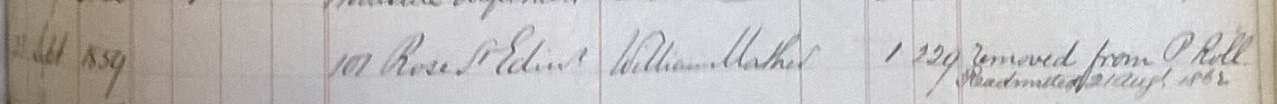

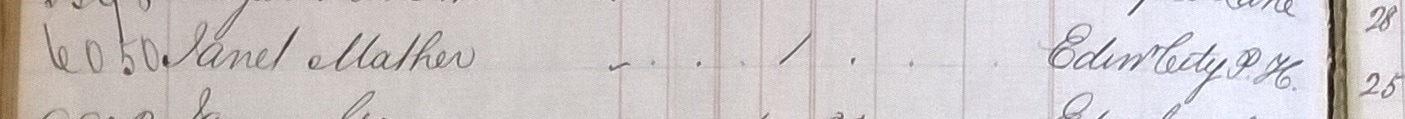

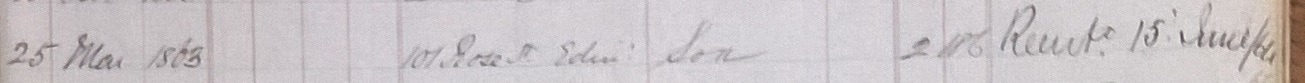

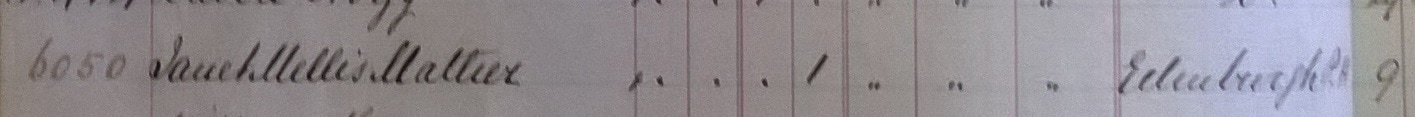

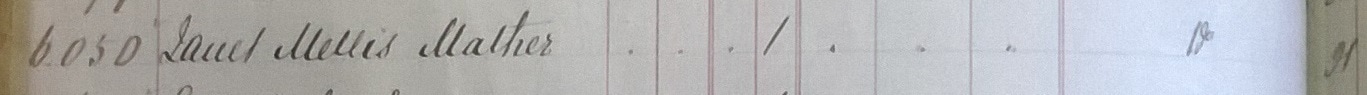

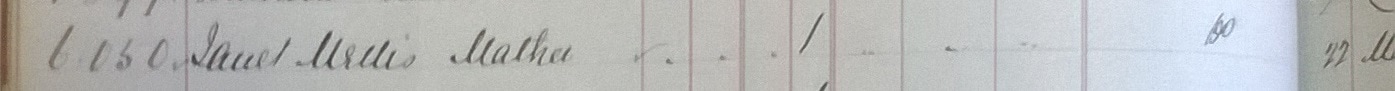

One hundred and fifty years ago today Janet Mellis Mather was admitted to the Edinburgh Poorhouse as a "lunatic pauper". This was not her first admission to an asylum. She had first been admitted to the Poorhouse on 16 August 1859, before being removed from the poor roll and released into the care of her son, William, 5 weeks later. Before being admitted to the Poorhouse, she had been living with William at the 101 Rose Street, Edinburgh.

William had been a bookseller and stationer since at least 1848, and continued in that trade until about 1864. He was still living at 101 Rose Street with his mother in 1861:

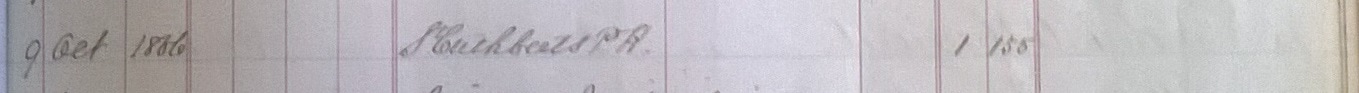

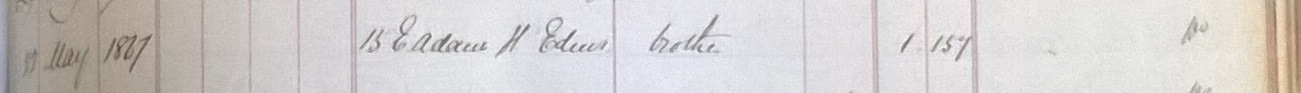

This didn't last, for just over a year later, on 21 August 1862, Janet was readmitted to the City Poorhouse This time she was in the poorhouse for 7 months. Less than 3 months after she had been admitted, on 14 November 1862, her son married Elizabeth Letheney in Edinburgh. She was released into the care of her son on 25 March 1863, before being readmitted on 15 June 1864 Her stay was much longer. On 9 October 1866, she was one of 24 patients transferred to St Cuthberts Poorhouse. It would appear that this was a temporary measure, as 13 of these patients were transferred back to the City Poorhouse just over three months later, on 21 January 1867. Conditions in the Edinburgh Poorhouse at this time were highly unsatisfactory, and the Parochial Board had decided to reorganise their arrangements. In August 1866, the Board decided to introduce so-called probationary wards for newly admitted inmates (paupers as well as "lunatics"), and plans were afoot to build a new Poorhouse at Craiglockhart, which would eventually open in 1867. It seems likely that Janet was moved as part of these new arrangements. Four months later, Janet was on the move again when she was released from the City Poorhouse: Her brother, William Ferrier Mather, was a grocer, as recorded in the Edinburgh Post Office Directory for 1865-66: Janet lived on for a couple more years, before dying aged 88 in 1869 in the Canongate. We can only speculate why she was taken in by her brother this time, and not her son, but it may have had something to do with William struggling to support his young family. Some time around 1865 he gave up his bookshop/stationery business. In 1871, he was a shop porter living at 93 North Bridge

By 1881, William was back in Rose Street, living at number 162. His children were no longer living with him. At this point, it's not clear if they had died or were living elsewhere.

William's fortunes continued to decline. By 1891, he and his wife were in the City Poorhouse at Craiglockhart. William was described as having formerly been a jobbing labourer. In 1893 his death was recorded aged 74 in the Colinton district - it seems likely he died in the poorhouse, which was in the Colinton area. His wife died in 1925, again in Colinton. She too may have spent the rest of her days in the Poorhouse, although without checking her death record or the City Poorhouse records at Edinburgh City Archives that cannot be confirmed. Sources:

This week we've been looking at the records of the Board of Supervision, a body established under the Poor Law (Scotland) Act of 1845 to implement the reformed system of poor relief in Scotland, and to act as an appeals body. The Board of Supervision lasted for 50 years until it was replaced when poor relief was transferred from Parochial Boards to local authorities. We came across one noteworthy case which illustrates several aspects of the operation of the Board of Supervision and the workings (or, in this case, failings) of the poor relief system. The case first appears with no mention of the name of the poor man: Thursday 30th November 1871 The Board were usually fairly scrupulous about gathering evidence, and as such many cases dragged out for extended periods. The next mention of the case is nearly two months later. Thursday, 11th January 1872 Four weeks later, the Board again considered the evidence Wednesday, 7th February 1872 When it came, the Chairman's verdict was devastating Thursday, 15th February 1872 Even through the bureaucratic politeness, it's clear that the Board believed that the Inspector's actions were a factor in the death of poor Alexander Macdonald. They didn't however go so far as to dismiss him - something that in other cases they were willing to do.

The Board of Supervision had a dual role - providing guidance to the local officers responsible for the operation of the Poor Law, and acting as an appeals body for applicants dissatisfied with the amount of support they received. We are currently indexing the appeals cases considered by the Board from its inception in 1845 to its abolition in 1895, and will be publishing the index in the next few months. Watch this space! In January 1843, the Conservative government under Sir Robert Peel established a Commission of Enquiry to study the Scottish system of poor relief. There had been growing concerns about the effectiveness of poor relief in Scotland, which at the time was in the hands of the Kirk Sessions of the Church of Scotland. A few months after the Commission was set up, the Church of Scotland split in the Disruption, with around 40% of ministers leaving to form the Free Church. This further eroded the position of the Church of Scotland, and made substantive reform inevitable. The earliest record of poor law in Scotland dates back to 1425 (not 1424 as is sometimes incorrectly stated). Those aged between 14 and 70 who were able to earn a living themselves were forbidden from begging, on pain of branding for a first offence and execution for a second offence: Of thygaris nocht to be thollyt Three years later, the king decreed that officials who failed to implement this act would be fined. In 1535, the system was further formalised. Poor relief was only to be granted to individuals in their parish of birth, and the “headmen” of each parish were to award tokens to eligible paupers, thereby introducing the concept of a licensed beggar. People caught begging outside of their parish of birth were subject to the same harsh penalties as before. An Act for punishment of the strong and idle beggars and relief of the poor and impotent was passed in 1579. This established the basic system of poor relief which was to continue for hundreds of years. Sic as makis thame selffis fuilis and ar bairdis or utheris siclike rynnaris about, being apprehendit, salbe put in the kingis waird and yrnis salang as they have ony guidis of thair awin to leif on If they had no means of sustenance, their ears were to be nailed to the tron or any other tree, and they were then to be banished. The penalty for repeat offenders was death. As for able-bodied beggars: all personis being abone the aige of xiiij and within the aige of lxx yeiris that heirefter ar declarit and sett furth be this act and ordour to be vagabundis, strang and ydle beggaris, quhilkis salhappyne at ony tyme heirefter, efter the first day of Januar nixtocum, to be takin wandering and misordering thame selffis contrarie to the effect and meaning of thir presentis salbe apprehendit; and upoun thair apprehensioun be brocht befoir the provest and baillies within burgh, and in every parochyne to landwart befoir him that salbe constitutit justice be the kingis commissioun or be the lordis of regalities within the samyne to this effect, and be thame to be committit in waird in the commoun presoun, stokkis or irnis within thair jurisdictioun, thair to be keipit unlettin to libertie or upoun band or souirtie quhill thai be put to the knawlege of ane assyse, quhilk salbe done within sex dayis thairefter. And gif they happyne to be convict, to be adjuget to be scurget and brunt throw the ear with ane hett yrne So “strong and idle” beggars were to be captured, imprisoned or put in stocks or irons, and brought before a court within 6 days. Upon conviction, they were to be burnt through the ear with a hot iron. The law puts in this caveat: exceptit sum honest and responsall man will, of his charitie, be contentit then presentlie to act him self befoir the juge to tak and keip the offendour in his service for ane haill yeir nixt following, undir the pane of xx libris to the use of the puyr of the toun or parochyne, and to bring the offendour to the heid court of the jurisdictioun at the yeiris end, or then gude pruif of his death, the clerk taking for the said act xij d. onlie. And gif the offendour depart and leif the service within the yeir aganis his will that ressavis him in service, then being apprehendit, he salbe of new presentit to the juge and be him commandit to be scurgit and brunt throw the ear as is befoirsaid; quhilk punishment, being anys ressavit, he sall not suffer the lyk agane for the space of lx dayis thairefter, bot gif at the end of the saidis lx dayis he be found to be fallin agane in his ydill and vagabund trade of lyf, then, being apprehendit of new, he salbe adjuget and suffer the panes of deid as a theif. In other words, the convicted idle beggar would be spared this punishment if someone offered him a job for a year. If he were to leave such employment without his master’s approval, he would be burned through the ear, but if convicted a second time, he would be put to death as a thief. The law then moves on to detail who should be subject to punishment. Not just beggars, per se, but also: all ydle personis ganging about in ony cuntrie of this realme using subtill, crafty and unlauchfull playis, as juglarie fast and lowis, and sic utheris, the idle people calling thame selffis Egyptianis, or ony utheris that fenyeis thame selffis to have knawlege of prophecie, charmeing or utheris abusit sciences, quhairby they persuaid the people that they can tell thair weardis deathis and fortunes and sic uther fantasticall imaginationes So people claiming to use witchcraft, self-styled “Egyptians” (i.e. Gypsies or Romanies), those claiming to have the gift of prophecy, charms, or fotune-telling. Other people to be punished include those with no visible means of support, minstrels, singers and storytellers not officially approved, labourers who have left their masters, those carrying forged begging licences, those claiming to be itinerant scholars, and those claiming to have been shipwrecked without affidavits: utheris nouthir having land nor maister, nor useing ony lauchfull merchandice, craft or occupatioun quhairby they may wyn thair leavingis, and can gif na rekning how they lauchfullie get thair leving, and all menstrallis, sangstaris and tailtellaris not avowit in speciall service be sum of the lordis of parliament or greit barronis or be the heid burrowis and cieties for thair commoun menstralis, all commoun lauboraris, being personis able in body, leving ydillie and fleing laubour, all counterfaittaris of licences to beg, or useing the same knawing thame to be counterfaittit, all vagabund scolaris of the universities of Sanctandrois, Glasgw and Abirdene not licencit be the rectour and deane of facultie of the universitie to ask almous, all schipmene and marinaris allegeing thame selffis to be schipbrokin, without they have sufficient testimoniallis Those hindering the implementation of the law would be subject to the same penalties. Having established the penalties, the Act requires all poor people to return to their parish of birth or habitual residence within 40 days of this act. Parishes were to be responsible for supporting their native-born paupers or those who had been habitually resident there for seven years, and were to draw up rolls of the poor. Aged paupers could be put to work, and punished if they refused. Children of beggars aged between 5 and 14 could be taken into service until the age of 24 for boys or 18 for girls, and could be punished if they absconded. An Act of 1597 on “Strang beggaris, vagaboundis and Egiptians” explicitly transferred responsibility for poor relief to Kirk Sessions. The 1649 Act anent the poore introduced a stent or assessment on the heritors of each parish to pay for poor relief. The 1672 Act for establishing correction-houses for idle beggars and vagabonds ordered the opening of correction-houses for receaving and intertaining of the beggars, vagabonds and idle persones within their burghs, and such as shall be sent to them out of the shires and bounds aftir specified in Edinburgh, Haddington, Duns, Jedburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Glasgow, Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, Ayr, Dumbarton, Rothesay, Paisley, Stirling, Culross, Perth, Montrose, Aberdeen, Inverness, Elgin, Inveraray, St Andrews, Cupar, Kirkcaldy, Dunfermline, Banff, Dundee, Dornoch, Wick and Kirkwall. By the time the Commission of Enquiry was set up, it was clear that provision was inadequate. The Commission’s exhaustive report (nearly 6000 pages in total, including evidence; even the index is 300 pages long!) made a series of recommendations:

in every such Parish as aforesaid in which the Funds requisite for the Relief of the Poor shall be provided without Assessment the Parochial Board shall consist of the Persons who, if this Act had not been passed, would have been entitled to administer the Laws for the Relief of the Poor in such Parish; and in every such Parish as aforesaid in which it shall have been resolved, as herein-after provided, to raise the Funds requisite for the Relief of the Poor by Assessment, the Parochial Board shall consist of the Owners of Lands and Heritages of the yearly Value of Twenty Pounds and upwards, and of the Provost and Bailies of any Royal Burgh, if any, in such Parish, and of the Kirk Session of such Parish, and of such Number of elected Members, to be elected in manner after mentioned, as shall be fixed by the Board of Supervision This meant that where a mandatory assessment was used to raise funds for poor relief, the Kirk Session no longer controlled the system, although it was still entitled to appoint up to six members of the Parochial Board. When the Act entered into force, 230 of 880 parishes were subject to statutory assessment. Within a year, that almost doubled to 448 (compared to 432 using voluntary contributions). By 1853, 680 parishes were using statutory assessments, compared to just 202 relying on voluntary contributions. The number of parishes relying on voluntary contributions continued to decline steadily, with only 108 doing so in 1865, and just 51 by 1890.

For genealogists, the implications are clear: after 1845, records of the poor will mostly be found among local government records, mostly held in local council archives around the country. That said, there are significant post-1845 poor records found among the Kirk Session records, not least because as we have seen, in many cases responsibility for poor relief remained with Kirk Sessions long after the Poor Law was enacted. However, the records of the Board of Supervision, being a national body, are held at the National Records of Scotland. One of the responsibilities of the Board of Supervision was to hear appeals against inadequate relief. These appeals are an excellent source for family history – they will tell you much about the individuals, as well as their families. They often include medical reports, information on the earnings of applicants and their families, names and details of children and the like. Before 1845, records of poor relief are more often with Kirk Session records. We saw in a previous post how it was possible to trace individual paupers in for instance Kirk Session accounts and other church records. Some of these records can provide excellent detail - we've seen examples of church poor relief records giving names, relationships, occupations, details of payment in kind, poor children being lodged out with other families and so on. They can be therefore be an excellent source for family historians, and should not be neglected. We are currently working on a national index to a particular set of Poor Law records from 1845 to 1894, which we plan to release later this year. |

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed