|

You might be reading this and asking what? Zetland -where’s that? It’s actually the traditional spelling for Shetland (to this day, Shetland postcodes all begin with ZE). And Zuill? It’s a variant rendering of Yuill. And the famous Scottish surname Menzies is not pronounced, as you might think, “men-zays”, but “ming-is”.

What is going on?, you might ask. Scots pronunciation can be notoriously unpredictable on occasion, particularly when it comes to placenames. To get an idea, how would you pronounce the following:

This is just one of the many features of Scots that English-speakers will find unusual. There are many other peculiarities of spelling, pronunciation and vocabulary that you may come across when researching your family history. Should you find a word you don’t recognise, and think might be Scots, the best place to look is the Dictionary of the Scots Language. Footnote: In case you were wondering, the placenames listed above are pronounced Mill-guy, Enster (or Ainster), Fittie, Kin-uch-er, and Cull-ain

1 Comment

We’ve briefly touched upon young communicants in a previous post. In most parishes, they’re listed either in Kirk Session minutes, or in Communion Rolls. Occasionally there are separate registers of Young Communicants, and these can sometimes be more informative. An example of such a register can be found in Ardler Quoad Sacra parish. As there aren’t all that many entries in the register, we thought we’d simply transcribe it for you. List of Young Communicants with notes of what is known of them in after life commencing from 1st Communion at Ardler Church 9th August 1885 1885 Communicated for 1st time 9th August

Spring Communion 1886

Spring Communion

Spring Communion

Spring Communion

Spring Communion

[NRS Reference CH2/884/6 p. 13-29] It was clear when I decided to attempt the A to Z Challenge that some letters were going to prove awkward. X was always going to be one of them. So hopefully you’ll forgive me for the slight cheat in this post. There is however a Scottish connection – albeit a rather tenuous one – to this phrase. Although he never used the phrase in Treasure Island, didn’t invent the idea of using X on a map to mark a specific location (which according to the OED dates back to at least 1813), and wasn’t even the first to use a pirate treasure map as a literary device (James Fenimore Cooper’s The Sea Lions used a similar plot device more than 30 years earlier), Robert Louis Stevenson is popularly associated with the idea of X marks the spot.

However, huge fan as I am of RLS, the real topic of this post is not literature but rather cartography – maps. Growing up, I was always fascinated by maps. My family owned a secondhand bookshop, and my parents would regularly bring home books for me. One day, though, my mum brought home a huge box of maps that she’d bought. Pretty soon, the walls of my bedroom were covered with maps of all sorts of places I’d never been – there was even one of the moon! The best maps, as well as being functional, were truly beautiful. One of my favourite collection of maps – a first edition of which I had the great privilege of owning when I was a bookdealer, albeit for a very brief period of time – is volume V of Joan Blaeu’s Theatrum orbis terrarum sive Atlas novus, known as Blaeu’s Atlas (or simply Blaeu in the book trade), originally published in 1654. Today, though, you don’t have to spend upwards of £5000 (!) for an original Blaeu to enjoy his work. You can view a digital version of it on the website of the National Library of Scotland. Beautiful as Blaeu’s maps are – and I still regret having to sell my copy – they are not terribly practical for family-history purposes. The lack of detailed, accurate maps of Scotland was officially recognised in the aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-6. George II ordered Lt-Col David Watson to produce a military survey of the Highlands of Scotland to assist with the suppression of the clans. One of Watson’s assistants was William Roy. The resultant work, known as Roy’s Military Survey of Scotland, is a landmark in cartography. For many parts of the Highlands it provides the only accurate map from the 18th century, at a time of massive change. Fortunately for us, the National Library have also digitised Roy’s masterpiece. The Ordnance Survey – the official mapping organisation in the United Kingdom – eventually emerged in part from the work of William Roy and his colleagues. The OS was a pioneer in cartography, and produced some incredibly detailed maps. They are usually referred to in terms of inches – one inch, six inch, twenty-five inch, quarter-inch. These figures refer to the scale used – the number of inches per mile – the largest the number, the greater the detail. These maps can be extremely useful when trying to identify particular places where your ancestors lived. Many small settlements, hamlets and farms no longer exist, or their names have changed beyond all recognition over the years. But consider this: the first edition of the 25-inch Ordnance Survey maps – dating from 1855-1882 – consists of 13,045 sheets. Even if you could find and afford to buy copies of them all, most people would find it highly impractical to keep them. Fortunately, the amazing staff of the NLS have digitised tens of thousands of Ordnance Survey maps. Even more usefully, they have georeferenced them, so that you can view maps of the same area from different periods. This makes it much easier to find maps of the particular district you’re interested in. You can find a list of the Ordnance Survey maps available on the NLS map site here, or you can search the map collection by placename using an interactive map, starting here. The Ordnance Survey itself provides tools to allow you to use maps to display information. We have produced a few examples for you. The first shows the people listed in the 1911 census for Kinclaven, in Perthshire. A number of the farms inhabited in 1911 are no longer to be found on modern maps, so we used the 19th century OS maps provided by the NLS to identify the precise locations where Kinclavenites lived. Our second example uses a modern map to show the locations of hundreds of archives and local libraries all over Scotland, very useful for finding where records of your ancestors might be held. Our third example involved mapping a client's ancestors. It's a useful illustration of just how detailed mapping can be. Contact us if you would like us to map your ancestors. We are in the middle of four years of centenaries of World War I, the war to end all wars which, sadly, was no such thing. Many people are naturally interested in the part their forebears played in the devastating conflict. I grew up knowing that my granny’s brother had been gassed in the war, and was give a one-way ticket to Australia, with the assumption that he wouldn’t live long. (He got his revenge by surviving long enough to raise a large family, many of whom I met when I visited Australia some years back.)

Partly in response to the centenary, many organisations have release records relating to World War I. Many of these are available free of charge, so we thought we’d list some of them. One of the most useful sites is the Scottish War Memorial Project, organised by the Scottish Military Research Group. Designed as a discussion forum, the site is arranged into geographical sections, with a remarkable amount of detail on war memorials, and the individuals commemorated on them. It is an ongoing, collaborative project, and is created entirely by volunteers. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission was established by Royal Charter in 1917, and is the official body responsible for maintaining cemeteries and memorials at 23,000 locations in 154 countries, honouring the 1,700,000 Commonwealth soldiers who died in World War I and World War II. The website includes a searchable database of memorials, which often include additional information to help identify your ancestors. Many Scots served in the armed forces of other countries, notably Australia and Canada. Library and Archives Canada have an excellent site with a searchable database of the service records of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Many Scottish-born soldiers served with the Australian and New Zealand armed forces. The National Archives of Australia and Archives New Zealand have built a dedicated website to help you find your Anzac ancestors, containing digitised service records. Unfortunately, a large proportion of the British service records from WWI were lost in a fire. And unlike Canada and Australia, the records are not available for free. Here at Old Scottish, we have developed innovative software to match records across a variety of free and subscription databases to help provide a fuller picture of Scottish servicemen, both those who died and those who survived. Some examples of how our systems can help join the dots are shown on our Auchterarder in World War I page. To mark the ongoing centenary commemorations, we are pleased to offer a special discounted rate for WWI research services – get in touch for a free initial consultation.

As mentioned in a previous post, for many years Kirk Sessions had responsibility for maintaining the poor of their parish. As well as administering financial support – often referred to as outdoor relief, in the sense of providing support outwith a poorhouse – some sessions also maintained records of visitations. These involved representatives of the Kirk Session periodically visiting the poor of the parish. Not many of these records survive, but where they do, they can be extremely interesting.

One parish where they do survive is Scone, in Perthshire. Included at the end of the Parochial Board letter book are a series of Notes on visits to the poor. There are 93 entries, so we thought we'd index them.

One entry – or rather series of entries – in particular, caught our attention. The entries start in 1846:

Isabella Whitelaw’s children, Lethendy Moar

Isabella Whitelaw had been arrested and brought before the Police Court, as reported on 23 April 1846 in the Northern Warder and General Advertiser for the Counties of Fife, Perth and Forfar:

Janet Gall or Cochrane, and Isabella Whitelaw, charged with several separate acts of theft some of which were committed beyond the bounds of Police, were handed over to the Sheriff.

Her conviction was reported a few months later:

Sheriff Court

All seemingly goes quiet for the Whitelaw children for a couple of years, but then we find some more entries in the poor visitations:

Isabella Whitelaw’s two children

This time, Isabella’s conviction is reported in the Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review

Isabella Whitelaw, Perth, accused of theft – aggravated by previous convictions, was sentenced to seven years’ transportation.

The National Records of Scotland’s 19th century solemn database adds a few more details: that Isabella also went by the name of Helen Panton, that her address was c/o Robert Mills, cadger, Coupar Angus, Perthshire, that she could not write.

We next hear of Isabella as she is transported to Tasmania on board the Aurora, on 22 April 1851. Her arrival in Tasmania is recorded in the Register of Convicts, on 10 August 1851. She is described as a Country Servant, 5 feet 4 inches, age 31, with a ruddy complexion, dark brown hair, brown eyebrows, hazel eyes, and medium facial features. She was a wart on her left arm at the bleeding place. Her conduct record suggests she wasn’t entirely a reformed character. She was charged for being drunk on October 25 1852. On November 2nd, she was sentenced to 6 months hard labour for being absent without leave. On December 3rd 1852 she was “delivered of an illegitimate child (Mary) at the Cascade Factory”. On 2 October 1854 she was sentenced to 12 months hard labour for absconding. 11 August 1855 saw her being sentenced to 3 months hard labour for being drunk on her master’s premises. A few months later, on 5 November, she was sentenced to another 12 months hard labour for absconding when on a pass. Once more, on 29 June 1857, she was sentenced to one month’s hard labour for being out after hours and absconding. Shortly after the birth of her daughter, Isabella was granted permission to marry Michael McDermott on 14 December 1852. We have not however been able to find a record of them actually marrying. Things however do appear to have eventually improved for Isabella, as she was again granted permission to marry on 2 December 1856, to William Way, a freeman. They were married at the All Saints Schoolroom on 23 December 1856. William was a cabinetmaker. We have not found any more records of Isabella Whitelaw, and do not know if she ever returned to Scotland or saw her children again. Isabella Whitelaw's story is an interesting illustration of how one record can lead to another, and can end up telling a fascinating story. Scotland has a long and proud education tradition. This is often traced back to the Scottish Reformation, which espoused the principle of universal education, with the call for a school in every parish. In practice this didn’t necessarily happen, but at the time it was a fairly radical idea.

But the roots of Scottish education reach back much further than 1560. Several schools still in existence today can trace their origins to the twelfth century (Dunfermline High School, High School of Glasgow, Royal High School Edinburgh, Stirling High School and Lanark Grammar School). Higher education also has a long history in Scotland. Before 1410, Scots had to leave Scotland to obtain a higher education. The most common destinations were England (Oxford and Cambridge), France (Paris and Orleans), and Italy (Bologna), although doubtless some Scots studied elsewhere. An excellent source for these early Scottish students is Donald Watt’s A Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Graduates to AD 1410 (Oxford, 1977). By 1410, the division of the Catholic Church with two rival Popes made it essential to found a seat of higher learning in Scotland itself. A group of masters, mostly graduates from the University of Paris, set about founding an institution in St Andrews, in Fife. Henry Wardlaw, Bishop of St Andrews, granted the school a charter in May 1411. At the time, only the Pope or the Emperor could grant university status, so Bishop Wardlaw wrote to Pope Benedict XIII seeking confirmation. On 28 August 1413, Benedict granted university status to what was now the University of St Andrews in the Bull of Foundation. St Andrews was to remain the only university in Scotland until Pope Nicholas V granted a papal bull to Bishop William Turnbull (a St Andrews graduate), authorising him to establish the University of Glasgow. In February 1495, Pope Alexander VI granted a bull to William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen and a Glasgow graduate, establishing King’s College in Aberdeen. The last of the four ancient universities of Scotland to be founded, the University of Edinburgh, had a different start in life. Unusually for the time, it was established as a civic institution, by Royal Charter of James VI, in 1582 as the Tounis College. They were to remain the only universities in Scotland for hundreds of years. These days, when around half of school-leavers go on to higher education, it’s easy to forget that for most of their history, universities were for a very few only. My own alma mater, the University of St Andrews, has doubled in size in the 25 years since I graduated. So it’s likely that few of your ancestors would have gone to university. If they did, however, there are records to be found, although they may not provide much information. One very useful source for identifying people who studied at St Andrews is James Maitland Anderson’s The Matriculation Roll of the University of St Andrews 1747-1897 (Edinburgh, 1905). This has been digitised by the Internet Archive and can be found here. The information included is very limited, but it can offer some confirmation that your ancestor studied at the finest university in the world. (That last sentence may contain some personal bias …) For students before 1747, there is Robert N Smart’s Alphabetical Register of the Students, Graduates and Officials of the University of St Andrews 1579-1747 (St Andrews, 2012), although this is not available online. The University of Glasgow has an excellent site dedicated to the history of the University. As well as background information, it includes a database of nearly 20,000 graduates to 1915. Many of these entries contain additional information about the lives and careers of Glasgow graduates. This is an ongoing project and is regularly updated by the University Archive Services, who welcome any contributions of photographs and information about individual graduates. The University of Edinburgh Library and University Collections maintains a database of Alumni. As the site itself acknowledges, it is far from complete. The Special Collections department holds the University archive which includes many other records of university life. There are also some printed registers of graduates which can also help track ancestral students. Several of them are available in digitised versions online: Alphabetical List of Graduates of the University of Edinburgh from 1859 to 1888 A Catalogue of the Graduates in the Faculties of Arts, Divinity, and Law, Of the University of Edinburgh, Since Its Foundation (Edinburgh, 1858) There are also a number of graduate rolls for the University of Aberdeen: Officers and Graduates of University and King's College, Aberdeen, 1495-1860 edited by Peter John Anderson (Aberdeen, 1893). Roll of the Graduates of the University of Aberdeen, 1860-1900 edited by William Johnston (Aberdeen, 1906) Roll of Graduates of the University of Aberdeen : 1901-1925 : with supplement 1860-1900 by Theodore Watt (Aberdeen, 1935) [We are unaware of any online version of this] Roll of Graduates of the University of Aberdeen : 1926-1955 ; with supplement 1860-1925 compiled by John Mackintosh (Aberdeen, 1960) [We are unaware of any online version of this] The individual universities may have additional information on some of their graduates, and it is always worth contacting their alumnus relations departments or libraries/archives to check, although you should always bear in mind that sometimes they may be unable to search their records due to a lack of resources, and that often the records themselves may contain limited information about your ancestors.

Scotland has long had a complicated relationship with alcohol. It is of course home to one of the most popular and prestigious alcoholic drinks in the world - whisky (uisge beatha). Brewing also has a long history in Scotland. Growing up in Edinburgh, I was always familiar with the distinctive smells emanating from the many breweries in town.

Scots also have a reputation - perhaps a little unfair, but also not entirely unwarranted - as a nation of drinkers. Official Scotland - or quasi-official Scotland, in the form of the Church - has long sought to regulate and control the temptations of alcohol. Kirk Session records are full of disapproving references to drunkenness and the evils of alcohol. Awareness of the hazards of excess alcohol consumption was widespread in the 18th century. William Hogarth's famous prints Beer Street and Gin Lane served to graphically illustrate the social ills associated with the Gin Craze. Production of alcohol was in many cases subjected to licences and taxation - although alcohol taxes were often lower in Scotland than in England. The nineteenth century saw the rise of the temperance movement. The founding figure in Scotland is generally considered to be John Dunlop of Maryhill, who established a society to campaign against "ardent spirits", advocating the consumption of less alcoholic drinks instead. Others - notably publisher William Collins - took a stricter view, calling for total abstinence from alcohol. The Scottish Temperance League was formed in Falkirk in 1844. Local groups sprang up in many parts of Scotland. One such was the Thornhill Total Abstinence Society, established in 1846 in Thornhill, not far from Falkirk. The minutes of the Society survive among the records of Norrieston Free Church. The records start with a statement of the Rules of the Society: Rules of the Thornhill Total Abstinence Society

Shrub was a form of alcoholic fruit liqueur, usually made with rum or brandy mixed with sugar and citrus juice or rinds. An exception was to be made for the consumption of alcohol in religious ordinances (such as wine during communion), or as medicine!

The records continue with a list of members from 1846 up to 1851. I have found family members in a similar record set in Edinburgh, where a subscription scheme was set up, and members who remained teetotal after 10 years were paid a share of the subscription proceeds. Were any of your ancestors teetotallers in Thornhill?

These days we often take surnames for granted, and it’s not always obvious that they were in fact invented. The earliest surnames in Scotland date back only to the 12th century, and in some parts of Scotland, they did not become fixed until much later.

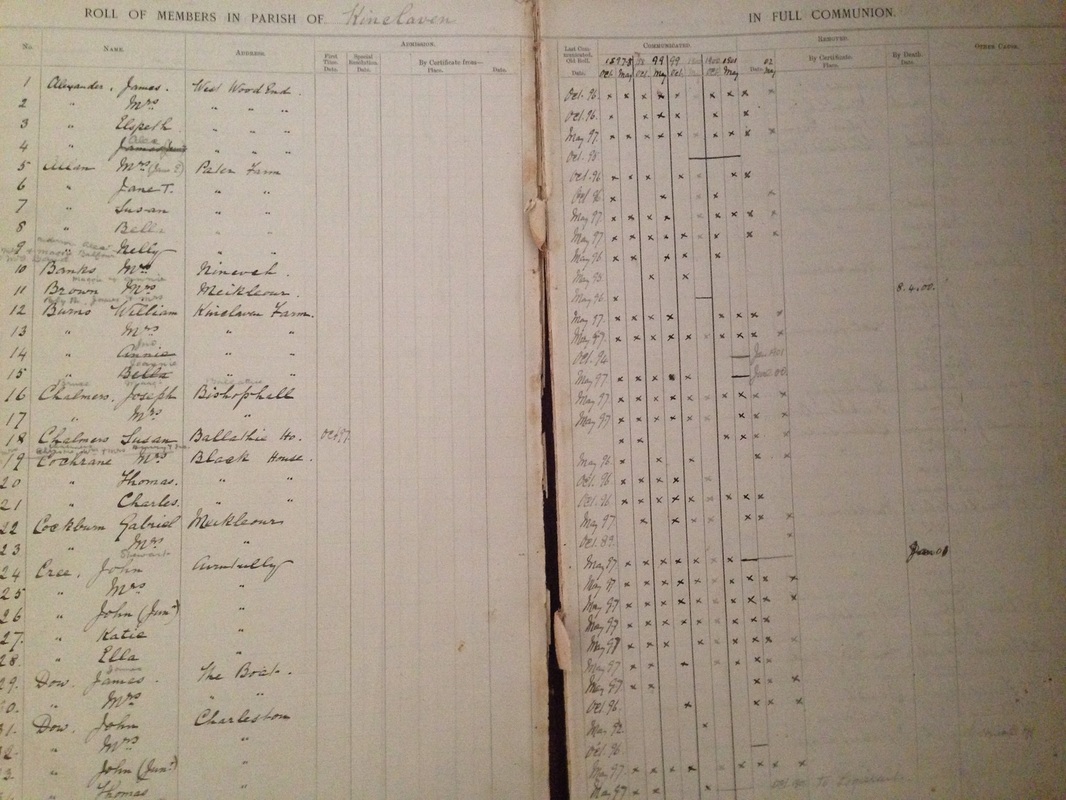

Broadly speaking, surnames can be grouped into five categories Patronyms (and occasionally matronyms) A patronym is literally a name derived from the name of the father (or more generally male ancestor). Similarly, a matronym is a name derived from the name of the mother. Originally, a patronym would have been used to distinguish between two different people with the same forename. The most stereotypically Scottish names – the Macs – are of course patronymic. Mac is Gaelic meaning “son of”. There are a few matronymic Mac names – an example would be MacJanet, of whom there were 20 in the 1841 census. Originally patronyms would have changed with each generation – as they still do in for example Iceland – but over time they slowly became fixed, first in Lowland Scotland, then later in the Highlands. Single-generation patronymics were still being used in Shetland as late as the early nineteenth century. Occupational names Many surnames are occupational in origin. The meanings of some are very obvious to modern readers – Farmer, Smith, Shepherd to name but three. Others are perhaps less obvious, as the occupations have largely disappeared (Fletcher means maker or seller of arrows), or because the modern occupation terms are spelled differently (Baxter means baker). Topographical names My great-great-grand grandmother was Margaret Carstairs, from Largo in Fife. Ultimately her name derives from Carstairs in Lanarkshire. The surname first appears in Fife, with the earliest record being of a John de Castiltarris (i.e. “of Carstairs”) appearing in 14th century Vatican records after being granted a benefice in north-east Fife. This is not as paradoxical as it may seem – the earliest progenitor of the name came from what is now Carstairs in Lanarkshire and moved to Fife. It’s worth bearing in mind that the earliest appearance of a topographical surname was probably not in the place in question. If you think about it, this is logical, as it makes no sense to refer to John of Carstairs in Carstairs itself – the surname only becomes meaningful outwith the place of origin. Nicknames or bynames Some of the most common surnames are nicknames or descriptive names. Some of them are obvious to English-speakers – Little, White for instance. Others are derived from Scots (such as Meikle meaning large) or Gaelic (Campbell, from Gaelic caimbeul meaning crooked mouthed). Ethnic names There are a number of ethnic names to be found in Scotland. Some are obvious – French, for instance. One of the most common names in Scotland is Fleming, a term originally applied to people from Flanders. Many settlers from Flanders came to Scotland in the 12th century, and today Flemings are to be found all over Scotland. Another common Scottish surname is Inglis, which means English. Even Scotland’s most famous novelist, Sir Walter Scott, bore an ethnic surname. There are many surnames and spelling variants to be found in Scotland. In our research over the last few years, we have recorded more than 8000 of them (a figure which grows on a daily basis). We have been carrying out a project in an attempt to understand the distribution of these surnames. Many surnames are fairly evenly spread around Scotland, while others are very heavily concentrated in particular areas. This can provide a useful hint if you’re not sure where your ancestor came from, although obviously it can only ever be a guide. At present, our algorithm involves looking at the number of times a given surname occurs in each county in Scotland (as well as in the cities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Dundee and Glasgow), and compares the frequency of the surname in each county with the frequency of the surname in the Scottish population as a whole. At present we are looking only at the 1841 census. In future, we hope to extend this technique to later census years, and also perhaps to individual parishes rather than counties as a whole. As you might imagine, this involves a lot of number crunching, and as such takes some time. We are gradually working our way through the alphabet, and you can see the results here. Communion is a sacrament recognised by most Christian denominations in remembrance of the Last Supper. In Scotland it was generally held twice a year. Parishioners were expected to attend, and repeated failure to do so could result in parishioners being removed from parish membership. In preparation for the sacrament, the Kirk Session would distribute communion tokens to would-be communicants. Without these tokens, parishioners were unable to take part in communion. Sometimes records were kept of the distribution of these tokens, but more commonly records were kept of attendance at communion itself. These records are generally referred to as Communion Rolls. Within the Church of Scotland, when people moved and sought to join the parish in their new place of residence, they generally had to produce a certificate (sometimes referred to as a testificate) from their home parish, confirming that they were communicants. To qualify for such certification, they had to have attended communion at least once in the previous three years. At their simplest, communion rolls are just lists of parishioners who attended communion. The earliest surviving rolls are merely lists of names. The oldest we have found is from St Madoes in Perthshire and covers the period 1596 to 1611. We have not found many surviving Church of Scotland communion rolls before the nineteenth century (5 in the 17th century, 7 more before 1750 and only 25 before 1800). They really start to become more common – and more useful – around the middle of the nineteenth century. We have identified around 3000 nineteenth-century communion rolls from the Church of Scotland. By the mid-1800s they were sufficiently widespread that two separate church stationers were producing printed forms to simplify the job of clerks in recording communicants. Printed Communion Roll [Kinclaven Parish, Church of Scotland, Communion Roll 1880-1894, held privately] By this time, communion rolls were also becoming more detailed. In addition to recording names, they regularly include occupations and addresses, and crucially information on admission to communion and disjunction.

There were several ways for an individual to be admitted to communion. They could be admitted as Young Communicants (sometimes referred to as Catechumens). This involved someone, usually the Minister or sometimes an Elder, testing their knowledge of scripture and religious doctrine, often after a series of lessons. The term Young Communicant may in some cases be somewhat misleading – in most cases, Young Communicants would be around 18 to 21, but we have found a few instances of individuals significantly older being admitted for the first time. Indeed some clerks recorded this form of admission as “First Time” or “By Examination”. The other main form of admission is by certificate. On moving to a new parish, church members would present certificates from their previous parish indicating that they were in communion with the church and not subject to scandal for misbehaviour. Some communion rolls only record the fact that an individual was certified, but others record the date and – more usefully – the parish that issued the certificate. This can help identify where an individual came from. Disjunction information can also be very useful. Sometimes clerks would simply record that an individual “Left” or was “Certified”. In some cases, the fact that an individual died was also recorded – in many cases the date or year of death is given. Disjunction information becomes much more useful when the clerk records the place the parishioner moved to. Usually it’s just a parish, but sometimes a full address is given, and other times the clerk will record that the individual emigrated. This can be very useful as sometimes it can be the only confirmation of the identity of a Scottish emigrant to for instance the United States. The completeness of information varies from parish to parish – and over time within the same parish. Even so, communion rolls can prove very useful in tracking individuals. An example is James Wilson, a farm servant. He was recorded with his wife Catherine Methven at Lochton in Abernyte, Perthshire. The communion roll notes that he had been admitted by certificate from Kilspindie in 1881. They were then certificated to Kinnaird in 1882, where they were found living at Kinnaird in the communion roll. They were then again certificated to Longforgan in 1883. The Longforgan communion roll describes James as a ploughman at The Mains and shows that the family were certificated onwards to Perth in 1885. If you look at census records for this couple, they were at Nether Durdie in Kilspindie in 1881 with 9 children. The second youngest, Jemima, aged 2, was born at Longforgan and the youngest, David, just a month old, was born at Kilspindie. By 1891, James was a farmer at Old Gallows Road in Perth (where he’d moved in 1885). Any attempt to track this couple relying solely on census and birth records would have missed their short stay in Kinnaird. Without the communion roll, this sojourn would have likely been unidentifiable. We are working on a project to extract and publish information from Communion Rolls. We have so far transcribed around 50 rolls from Perthshire. You can see an example of the sort of information contained in the communion roll for Kinclaven 1880-1894. (Note that this particular communion roll is held privately, and is not recorded in any archive catalogue.) You can also browse the communion rolls that we have transcribed so far here. Quarter days are the four days used to mark the four quarters of the year. Scottish quarter days, also known as term days, have always been different from English or Irish quarter days. They originally occurred on holy days, although they have now been fixed by the Term and Quarter Days (Scotland) Act 1990 on the 28th days of February, May, August and November. Historically, the quarter days were used for hiring fairs (to hire farm servants), rental contracts, the payment dates for rent, loan interest and salaries and stipends. As such, their names appear in all sorts of historic records, in which the writers and the intended readers would know exactly what they meant. As a modern researcher, it’s therefore very useful to know what they were. The four quarter days traditionally were: Candlemas Candlemas fell on February 2. It marked the Feast of the Presentation, marking the occasion when Mary and Joseph took the infant Jesus to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem 40 days after his birth. In pre-Reformation Scotland, the feast was marked by candlelit processions by mothers who had given birth the previous year. The term is still used today by among others the University of St Andrews, as the name of one of the semesters. It coincides with the Celtic celebration of Imbolc. Whitsunday Whitsun fell on May 15 under the Gregorian Calendar (May 26 under the Julian Calendar before 1599). It commemorates the giving of the law to Moses at Sinai. In respect to genealogy, valuation rolls were in force from Whitsun to the day before the following Whitsun. Whitsun also often coincided with the celebration of the spring communion. Lammas The name Lammas comes from the Anglo-Saxon half-mas, or loaf-mass. It is celebrated on August 1, and marks the first fruits of harvest. It coincides with the Gaelic festival of Lunastal, when in the Highlands it was traditional to make a special cake known as a lunastain. It appears in a celebrated ballad, The Battle of Otterburn, of which the opening verse is: It fell about the Lammas tide, The name is still used in the context of the Lammas Market, held in St Andrews in Fife in August every year, and purportedly the oldest surviving street market in Scotland.

Martinmas Martinmas was November 11. It was originally the feast held to commemorate Martin of Tours, a celebrated 4th century bishop and hermit. St Ninian, an important figure in the Christianisation of Scotland often overshadowed by the better-known St Columba, studied at Marmoûtiers, St Martin’s monastery, and he dedicated one of the earliest churches in Scotland to St Martin. Martinmas is still used as the name of the winter semester at the University of St Andrews, and was historically used by the other ancient universities of Scotland (Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh). The date is of course now better known as Remembrance Day, marking the end of the First World War. |

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed