|

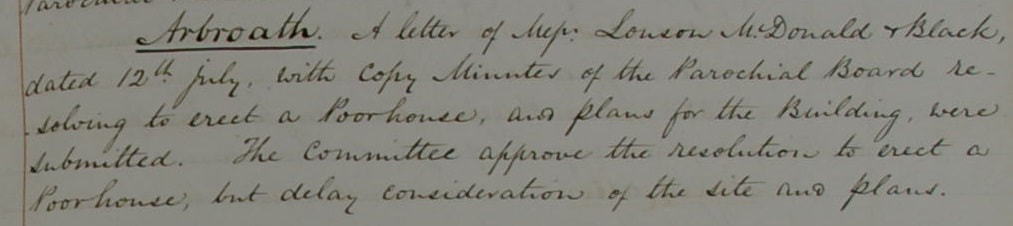

In 1855, Arbroath Parochial Board was considering building a poorhouse: 19th July 1855 The Board of Supervision, a national organisation based in Edinburgh, was responsible for overseeing implementation of the Poor Law Act of 1845. One of its statutory duties was to consider and approve plans for poorhouses. The Board evidently suggested some alterations to the plans: 24th October 1855 Eight days later, the Board met again, and signed off on the plans: 1st November 1855 The subject then seems to be dropped, for the Board of Supervision minutes do not seem to mention Arbroath's proposed poorhouse for quite some time. More than eight years later, though, Alexander Brown and six fellow Arbroath ratepayers write to the Board of Supervision with a complaint that seems a familiar one 150 years later: 10th December 1863 This rebuke from the Board of Supervision seems to have prompted the Parochial Board finally to push on with their plans to build a poorhouse, this time as a Combination Poorhouse in conjunction with St Vigeans parish: 8th September 1864 A week later, after receiving further correspondence from the builders, together with a map of the site, the Board approved of the site: 15th September 1864 Even that was not the end of the matter. It was another five months before the plans were finally approved by the Board, nearly ten years after the initial plans were submitted by the Parochial Board: 9th February 1865 Shortly thereafter, the Arbroath Combination Poorhouse finally opened, some ten years after the plans were first submitted. Sources:

0 Comments

This week we've been looking at a wide range of poor law records in preparation for the launch of a new project (coming soon: watch this space). The records of the Board of Supervision - which among other things was responsible for oversight of the operation of the poor relief system in Scotland following the Poor Law Act of 1845 - make for fascinating reading. There are obvious parallels with modern welfare systems, and the tensions inherent in them. The Board's Sixth Annual Report, published in 1851, includes a report on the Easter Ross Combination Poorhouse, which had been opened the previous year. Written in a dry, slightly bureaucratic style, it describes the progress of what was the first poorhouse in the Highlands: The Easter Ross poorhouse was erected by nine contiguous parishes. The house was opened on the 1st of October 1850, and the first pauper was admitted on the 11th of that month. I visited the house on Monday and Tuesday, the 4th and 5th of August, and communicated with the inspectors of Tain, Tarbat, Fearn, Logie Easter, Kilmuir Easter, and Rosskeen. Since 11th October 1850 to 5th August, forty-eight paupers had been admitted to the poorhouse, some of them having in the course of that time, left the house, of their own accord, and been again admitted. Five of the forty-eight paupers died at the ages of 70, 50, 71, 20 and 72 years. The immediate causes of the deaths of four were bronchitis, hydrothorax, dysentery, chorea, or St Vitus’s dance. In the fifth case, the cause of death was not entered in the record, the pauper having only very recently died. Three of the forty-eight paupers had been removed elsewhere – one of them to a lunatic asylum – four had left the house of their own accord, and had not applied for re-admission: thus at the date of my visit, there were only thirty-six paupers in the house, leaving accommodation vacant for upwards of 120. The appearance of the inmates was good, and the cleanliness maintained throughout the establishment unexceptionable. The governor appears to be well suited for the office, and keeps all his books with great neatness and regularity. The objectionable points of the management are:

The complaint that inmates are often free to come and go as they please suggests that the reporter, Mr Peterkin, was of the view that paupers should be kept out of sight. Another obvious concern - a common theme today for welfare systems - is the cost. Peterkin continues: During the first two quarters of the operation of the poorhouse, the parochial board of Rosskeen issued sixty orders for admission to paupers on the roll; of that number, only ten availed themselves of the order – all the others refused to enter the house, and were consequently struck off the roll. Seven of them were, however, subsequently admitted to outdoor relief, but four at smaller allowances than they formerly had. All the others, forty-three, have supported themselves since without parochial assistance. It appears, too, that adding the out-door allowances, which (if there had been no poorhouse), would have been payable to the paupers who took advantage of the orders of admission, to the allowances of the paupers who have supported themselves without parochial relief, for two quarters and a half, a sum would be given equal to £59 19s. whereas, the exxpense of the paupers in the poorhouse, for maintenance and general expenses for three quarters, amounted to only £58 8s 1 1/4d. Thus Rosskeen has afforded relief to their paupers, under a poorhouse system, for three quarters of a year, for a less sum than that which would have been required to give outdoor relief for two quarters and a half, supposing no poorhouse had existed. This also shows that refusal of a place in the poorhouse could lead to all poor relief payments being withdrawn. The fact that many people chose to do so suggests that the poorhouse was viewed as a last resort by desperate people. The Board of Supervision handled appeals from people claiming the relief offered them was inadequate. Many of these appeals were rejected on the basis that the applicant had been offered a place in the poorhouse. Peterkin's closing remarks also have contemporary counterparts, in the notion that those on benefits have it easy compared to the working population: Another subject was frequently touched upon by those with whom I conversed on the matter of poorhouses, namely the diet of the inmates – in regard to which, a rather general misapprehension seems to prevail, many conceiving that the diet in a poorhouse would be of such a superior description to that of the people of the country where the poorhouse would be situated that a desire would be created among the paupers of participating in it, although they might have serious objections to the confinement and discipline of the poorhouse itself. Should poorhouses ever spring up in the Western Highlands, the dietary of the Easter Ross house, which is appended, might be adopted by them, except perhaps barley-broth and pea soup, neither of which, so far as I know, are articles of food in general use among the people of the Western Highlands and Islands. Potatoes, herring, oatmeal, and mil would seem to be the requisites of a diet-table for a poorhouse there. So what was the menu provided for inmates of the Easter Ross Poorhouse? Residents were grouped into three classes: aged and infirm; adults; and children. Class 1: Aged and infirm persons

Class 2: Adult persons

Class 3: Children

Upcoming family history talks and events in Scotland, 28 November - 4 December 2016

Note that there may be a small charge for some of these events, and some may be for members only. We will be publishing lists of upcoming talks and events regularly - if you are organising a talk or event relating to Scottish genealogy or history, please let us know and we will be happy to add your events to our list. Monday, November 28 2016, 3 pm Early Irish Migrations to Scotland - Difficulties, Debates and DNA Dr Catherine Swift (Mary Immaculate College, Limerick) Venue: Room 208, 2 University Gardens, Glasgow Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies Monday, November 28 2016, 7.30 pm Rossie: The Loch That Disappeared Prof David Munro Venue: Age Concern Building, Provost Wynd, Cupar Monday, November 28 2016, 7.30 pm Migrants, Benefits and Tax-Avoidance in Glenalmond, 1700-1900 Robin Urquhart, National Records of Scotland Venue: Pitcairngreen Village Hall West Stormont Historical Society Monday, November 28 2016, 7.30 pm The Pentland Way, a Walk with History Bob Paterson Venue: Gibson Craig Memorial Hall, Lanark Road West, Currie Currie & District Local History Society Monday, November 28 2016, 7.30 pm 21st Century Archaeology: Trowels, Tourism and High-Tech Trends Dr Jeff Sanders Venue: Millennium Room, Cramond Kirk Hall Dr Jeff Sanders, DigIt 2017, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, on why the past is good for our future and providing a sneak peek ahead of Scotland’s Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology Tuesday, November 29 2016, 1 pm Franciszek Smuglewicz’s James Byres of Tonley and His Family: A Scottish Antiquarian Network in Eighteenth-Century Rome Dr Lucinda Lax (Scottish National Portrait Gallery) Venue: Room G16, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, William Robertson Wing, Old Medical School Scottish Centre for Diaspora Studies Diaspora Studies Graduate Workshop Series Tuesday, November 29 2016, 7.30 pm Fundamentalisms Kilmarnock Origins - Thomas Whitelaw 1840-1917 Mark Nixon Venue: Kilmarnock College, Hill Street, Kilmarnock Kilmarnock & District History Group £2 donation for non-members Wednesday, November 30 2016, 4 pm Textiles of the Viking Age Eva Anderson Strand, Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen Venue: Lecture Theatre (109), Gregory Building University of Glasgow Wednesday, November 30 2016, 6 pm Improvement and Landscape: Landownership in Eighteenth-Century Scotland Micky Gibbard, PhD student, University of Dundee Venue: Burghfield House, Cnoc an Lobht, Dornoch University of the Highlands and Islands Centre for History This seminar is being given as part of the relaunch of the Centre for Scotland’s Land Futures. The evening will commence at 6pm with a wine reception and will be followed by the relaunch and the seminar. More details will follow and booking is essential. Thursday, December 1 2016, 6 pm - 7.30 pm Fashion and Function: Costume and textiles from the Dalrymple family collection Emma Inglis, Curator, NTS Venue: Newhailes House, Newhailes Road, Musselburgh, EH21 6RY £8, including complimentary glass of wine. Limited space, book online Thursday, December 1 2016, 7 pm The History of Scottish Gold and Silversmiths & their marks George Dalgleish Venue: The 252 Memorial Hall, Betson Street, Markinch Free to members and £2 for non members Thursday, December 1 2016, 7.30 pm Wark Castle Eric Grounds Coldstream and District Local History Society Saturday, December 3 2016, 10 am - 12 pm Health and history: Using medical records in genealogical research. Louise Williams Venue: Scottish Genealogy Society Library, 15 Victoria Terrace, Edinburgh, EH1 2JL Health records can be another source of information to help further your family’s history but they are not found on the usual websites, etc. Louise Williams, Archivist will show what these records contain and where to find them. Saturday, December 3 2016, 2 pm To Prove their kindred here The Irish Office of Arms in the 18th Century Colette O'Flaherty - Chief Herald of Ireland Venue: Royal Scots Club, Abercromby Place, Edinburgh The Heraldry Society of Scotland Saturday, December 3 2016, 7:00pm for 7:45pm St Andrew Dinner Elizabeth Roads, LVO - Snawdoun Herald, Lyon Clerk and Keeper of the Records Venue: Royal Scots Club, Abercromby Place, Edinburgh The Heraldry Society of Scotland We've written before about the evolution of Poor Law in Scotland. The 1845 Poor Law (Scotland) Act established detailed rules for the provision of poor relief, with a central body - the Board of Supervision - responsible for monitoring its implementation. Before 1845, poor relief, such as it was, was greatly decentralised - parishes were responsible for their own paupers, and the rules were rarely outlined in much detail. However, a meeting of the heritors, minister and Elders of the parish of Forgue parish in Aberdeenshire did record the rules for poor relief as established by an earlier meeting of freeholders of the county held in Aberdeen on June 6 1751. Like many Kirk Session minutes, the entry starts with a preamble detailing the sederunt (i.e. the names of those in attendance), and the reason for the meeting: At Manse of Forgue the 28th of June 1751 years, being the time fixed for the meeting of the heritors, minr & elders of the parish of Forgue for taking the state of the poor of sd Parish under consideration, in consequence of the repeated Intimations of the Sherriff Substitute of the County of Abdn, there being pnt Theod Morison of Bogny, Alexr Duff of Hatton, Mr Willm Irvine of Corniehaugh, George Phyn of Corse, Mr Alexr Forbes minr, And Harper, Geo Morison, Alexr Horn, Jas Anderson & Alexr Muir elders; When the Resolutions of the freeholders of the County of Abdn met at Abdn the 5th of June curt anent Vagrants & begging poor, wt abstracts of the Laws & proclamations of Council on that Subject were laid before the said Meeting; and in consequence of the sd Laws, Resolutions and repeated Intimations of the Sherriff, the Meeting thought it incumbent and necessary for ‘em to make a Record containing the Resolutions as to the Managemt of the poor, the publick funds and Collections of sd Parish, Present State of the poor and quarterly allowance formerly given ‘em; and to settle what further will be necessary for maintenance of such poor as will be subsisted by the parish of Terms of sd Laws, Proclamations and Resolutions. One little thing that struck me about this passage - and it's repeated throughout the rest of the minute - is the use of 'em for them. Like many minutes of this period, the text is full of abbreviations - paper was expensive (and perhaps some clerks were keen to minimise their workload), but this is the earliest use of 'em I've come across. The rules as laid out show some of the same preoccupations as contemporary framing of welfare systems, such as benefit fraud: 1. The Heritors, minr and Elders agree to use all possible means to detect all Impostors, and to prevent any person from being entered upon the poor Roll of sd parish but such as are unable & uncapable to maintain emselves either in whole or in part. The next clause is reminiscent of modern concerns about the "workshy": 2. That such as are able to work for a part of their Subsistence either at Husbandry or Manufactures, shall be obliged to do it, & supply’d for the remainder only; and if they refuse to work confirm to their Ability, that they are to have no Relief and to be prosecuted as Law directs. Families were expected to look after their own: 3. That parents when able are to maintain their children, and children their parents, in whole or in part, which if they refuse to do they are to be prosecuted before the Sherriff in terms of Law. The fourth clause shows that paupers were expected to repay their benefits, even after death. Parish accounts often include details of roups (auctions) of the goods of paupers who died, showing that poor relief was often a loan, rather than a grant: 4. That all Persons before they be put upon the Poors Roll be made to convey to the Kirk Session of the Parish whatever effects they shall be possessed of or intituled to at Death (unless on the event of their circumstances being altered by succession or legacies sometime before their Death, or upon their repaying to the Session the full Extent of what was given out for their former support), in which Event the Session is to repone em, but in no other event are they to repone who once accept of a full subsistence; and such as accept of a partiall subsistence may be reponed by the Session at any time upon prepaying what was formerly given them. We have 18th-century benefit caps: 5. That no more shall be allowed to any person but one peck of meal for each week, or the value thereof, unless upon extraordinary occasion & when done by consent of heritors, minr and Elders. And "work for benefits". These sort of schemes were quite common - we've come across one parish that turned this approach into a competition, with a premium (meaning a prize) for the best spinners/weavers: 6. And in order to afford work to such of the poor as have not trades to buy flax or wool to ‘emselves, the Session agrees, that if no manufacturers will trust em, they will be Caution to such manufacturers or Merts for the value of the wool or Lint given to such Poor by their Advice, if not returned when manufactured, in order to put such poor people aworking what they can for their own Support, that the Parish may be relieved. Parishes were keen to avoid liability for incomers, instead returning them to their parish of origin. (Resetter in this context means someone providing support, shelter or protection). 7. The meeting further agree that none shall be received upon the poors Roll but such as have resided three years in the Parish; and if any poor shall intrude the Constable for the District be called to remove ‘em; and that the Resetters of any such be prosecuted. Landholders were liable for checking the papers of their tenants, and - if they fell ill and became unable to work - for returning them to their home parishes: 8. The Meeting also agree that every Heritor, tenent or subtenent that shall bring in any person upon the Parish who shall become uncapable to maintain emselves before the three years of Residence shall expire, by which they are intituled to Charity, whoever brings them into the parish shall be bound to maintain such Persons untill he transmit ‘em to their legall place of Residence for their maintenance; and that none shall be resett as a tenent or subtenent, but such as bring along with them certificates from the Parishes where they formerly resided. Children found begging and orphans could be forced into bonded labour in return for food and clothing: 9. And as by the Laws it is enacted, that if Children be found begging under the age of fifteen, any person may take such Children before the Heritors, minr & Elders, & record their Names & enact emselves to educate such Child to trade or Work, such Child shall be oblidged to serve the person until the 30th year of his or her age for meat & cloath, and this not only to extend to the Children of Beggars but also to poor Children whose Parents are dead, or with consent of the parents if alive; if any such Children be found, the meeting agree that the Law in Relation to ‘em take place. Poor relief was funded from church collections. Even in 1751 - nearly a century before the Poor Law (Scotland) Act was passed - there was concern that collections were insufficient to meet the needs of poor relief. (In fact, the 1845 Act was at least partly a consequence of the Disruption of 1843 and the formation of the Free Church - Church of Scotland parishes were responsible for poor relief for everyone in the parish, regardless of which church they belonged to: the Disruption meant that an ever-smaller number of people (Church of Scotland congregations) were responsible for poor relief. The 1845 Act stipulated that where a mandatory assessment was levied, responsibility for poor relief was transferred from Kirk Sessions to the newly established Parochial Boards: 10. They further resolve, that in the Event of the Congregation withdrawing the ordinary Collection, which formerly was the only support the poor had, every labouring servant if draws ten pounds scots of fee or above, shall be yearly assessed in six shillings Scots, and every servt that draws ten merks in thre shillings Scots, and every Grassman that pays 20 merks & below in 3 shillings Scots, and from 20 pounds to fifty merks yearly rent in 6 shill Scots, the masters to be accountable for the servt’s proportions which is to be put to accts of their wages; and it is not doubted by the principal Tacksmen will continue their Collections as formerly, as the maintenance of the poor will at last recur upon ‘emselves. The final clause stipulated that penalties for moral transgressions were to be fixed, and used for poor relief. This particular clause is a little unusual, in that it makes explicit that "sinners" could avoid ritual public humiliation by paying an additional penalty, an option that would only be available to relatively well-off parishioners. It was in fact a common practice, but it's usually not explicitly mentioned in the records. 11. They further agree that the least fine that shall be exacted from any fornicator shall be five pounds Scotch; and it is the Opinion of the Heritors that the minr and Sess when they think fit may dispense with the public appearances upon the stool for paymt of a Guinea each; which sums when so paid, are to be annually applyd for maintenance of the Poor. And that the minr and session before Absolution require the Parents of Children thus begotten to enact emselves & find Caution to free the Parish of the Charge of the Children; and in Case of their Refusal, to cause the Constable summon every Person refusing before the Sherriff of Abdn and transmit to the pro[curato]r fiscal an Extract of their judicial confession in order to have the law there anent enforced. It's striking to see many of the current concerns about benefits payments reflected in rules laid down over 250 years ago. These rules help clarify the position many people found themselves in the 18th century, usually through no fault of their own. It's also a useful guide to the practical operation of poor law in Scotland 90 years before national rules were codified in the 1845 Act for The Amendment and better Administration of the Laws Relating to the relief of the Poor in Scotland.

This week we've been looking at the records of the Board of Supervision, a body established under the Poor Law (Scotland) Act of 1845 to implement the reformed system of poor relief in Scotland, and to act as an appeals body. The Board of Supervision lasted for 50 years until it was replaced when poor relief was transferred from Parochial Boards to local authorities. We came across one noteworthy case which illustrates several aspects of the operation of the Board of Supervision and the workings (or, in this case, failings) of the poor relief system. The case first appears with no mention of the name of the poor man: Thursday 30th November 1871 The Board were usually fairly scrupulous about gathering evidence, and as such many cases dragged out for extended periods. The next mention of the case is nearly two months later. Thursday, 11th January 1872 Four weeks later, the Board again considered the evidence Wednesday, 7th February 1872 When it came, the Chairman's verdict was devastating Thursday, 15th February 1872 Even through the bureaucratic politeness, it's clear that the Board believed that the Inspector's actions were a factor in the death of poor Alexander Macdonald. They didn't however go so far as to dismiss him - something that in other cases they were willing to do.

The Board of Supervision had a dual role - providing guidance to the local officers responsible for the operation of the Poor Law, and acting as an appeals body for applicants dissatisfied with the amount of support they received. We are currently indexing the appeals cases considered by the Board from its inception in 1845 to its abolition in 1895, and will be publishing the index in the next few months. Watch this space! We've written before about the 1845 Act for The Amendment and better Administration of the Laws Relating to the relief of the Poor in Scotland, which as the name suggests changed the way in which Poor Laws operated in Scotland. As well as formalising on a statutory basis the operation of what would over time evolve into the modern benefits system we know today, the Poor Law (Scotland) Act 1845, as it is often referred, led to the establishment of Parochial Boards in each of the parishes of Scotland. This laid the foundations for the established of local, civil government in Scotland. Under the 1845 Act, Parochial Boards were responsible for administering poor relief. Parochial Boards would meet regularly to consider the state of Poors Funds in their parish, and to discuss applications for relief. Poor relief was paid by Parochial Boards, which were always keen to minimise their expenditure. Liability was determined by the long-established - and often contentious - system of settlement. While in theory the rules of settlement were relatively clear, there was always room for disputes between Parochial Boards keen to avoid spending their limited resources. As with Kirk Sessions determined to find someone to pay for illegitimate children, it was all about the money. In most instances, determining the parish of settlement of a pauper or applicant for relief was fairly straightforward - after all, most people didn't move around all that much. That was not, however, always true, as the case of George Thomson shows. The first time we come across George is in the Treasurer's Accounts of Drumoak parish, in Aberdeenshire: 1847, June 13 Three weeks later, he's mentioned again: 1847, July 4 Another three weeks later, he's mentioned in less happy circumstances 1847, July 25 George has died, and his widow is now in receipt of parochial aid. Another three weeks passes, and George is no longer mentioned by name Friday 13 August 1847 In order to qualify for parochial relief under the 1845 Act, George would have had to apply to the Parochial Board, satisfying them that he was in genuine need, and that he was settled in the parish. At first, the Parochial Board minute is not particularly interesting: Church of Drumoak 13 August 1847 However, the detail provided by George in his account is remarkable: That George Thomson, late husband of Ann Gillespie, was born at Little Mill of Cairney, that his father George Thomson is still alive and is resident at Foggy-Moss in said Parish. That he left his father’s when 13 years of age to be servant to Joseph Horne in Netherton of Cairney, with whom he resided six months; that he then went to serve John Christie in Busswarney in the Parish of Cairney, where he resided 2 ½ years; that he afterwards was in the service of Isaac Robertson, Banks of Cairney, 6 months; that he then went to Alexander Christie, Gangdurnas, parish of Cairney, with whom he resided 6 months; and thence to Charles Bruce in Broadland of Cairney, whom he served six months. That he then removed from his native Parish and entered the service of James Pirie, Culithie of Gartly, with whom he remained for 2 ½ years; that he afterwards went to the Revd Mr Leslie, assistant to the Minister of Rathven, where he remained 6 months; that he then went to James McCulloch, Cleffes in the parish of Grange, and continued with him 6 months; that he thence went to work with a contractor in whose service he worked in different parishes for short periods, and then removed to Fyvie for 6 or 8 weeks, and then to the parish of Belhelvie where he resided with a William McDonald for about 15 months; that he then resided six months with William Stronach carpenter in the parish of Nigg; that he thence removed to the parish of Fordoun and lived with Deacon Bruce innkeeper, Auchinblae about a month; that he then resided with Peter Laing in Banchory Ternan a month, and went to Kincardine O’Neil, where he lodged in the house of William Cooper for about six months. That he then removed to Banchory Ternan and was married 20 June 1840 to Ann Gillespie. That from Martinmas 1841 to the month of September 42 he earned his livelihood by working at Countesswells in the Parish of Peterculter or Banchory Devenick, visiting his family every Saturday night and continuing with them till Monday morning, as long as they resided in Banchory Ternan. That on the 7th of June 1842 his wife and family removed from said Parish of Banchory Ternan to this parish (Drumoak), he himself continuing to earn his livelihood at Countesswells, residing first in the house of Archibald Leslie and then in that of Alexander Watt, crofters in Loanhead of Countesswells. That he continued as before visiting his family every Saturday night and continuing with them until Monday morning till the month of September 1842 when he took up his regular residence in this parish, and resided till his death on 11th July 1847. Clearly George moved around quite a lot. Based on this declaration, the Board decided that they were not liable for relief payments: The Board taking the matter under consideration were of opinion that his widow and family had no claim upon this parish, but that Cairney was the parish of settlement, and instructed the Inspector to forward a statement of the case to the Inspector of said parish of Cairney. Although the Board did not believe they were liable, they continued to make payments to Ann, as we can see if we return again to the Treasurer's accounts: 1847 Octr 3 Seven weeks aliment to Widow Thomson, £1 1s The day after making this last payment, the Board met again to consider this case. Ann offered some more information about her circumstances: Drumoak 24 February 1848 While the Board waits for a response from the Inspector at Cairney, they continue to pay George's widow Ann: 1848, March 26 By 4 weeks aliment to Widow Thomson, 12s They didn't have to wait too long for a response Drumoak 12 May 1848 Apparently the Inspector at Cairney is not keen to pay for Ann's maintenance either. Meanwhile, the bills continue to mount for Drumoak 1848 July 30 By Widow Thomson’s 8 weeks aliment, £1 4s Five months later, the Board meets again Drumoak 31 Oct 1848 Cairney Parochial Board decide to call Drumoak's bluff, refusing outright to pay anything. Drumoak respond by calling in the lawyers, and going to court. In the meantime, they continue to pay Ann 1848 Finally, two and a half years after George initially applied for temporary relief, a resolution of sorts is achieved in court: Drumoak 31st January 1850 The treasurer of Drumoak records the payment received from the lawyers 1850 Jany 31 Now that liability has been established on the park of Cairney, the Parochial Board are perfectly happy to continue making payments to Ann 1850 Feby 10 By cash to Wid Thomson 4 weeks aliment, 12s Having initially denied liability, Cairney Parochial Board accept the court ruling, and reimburse Drumoak 1850 July 14, Received advances made to Wid Thomson by this Session on account of the Parish of Cairney, £3 15s 9d As well as providing an extraordinary amount of information about the working life of George Thomson, and the domestic arrangements of his family both while he is alive and after he dies, these entries also give a good illustration of how the system of poor relief operated in Scotland after the reforms of 1845.

As mentioned in a previous post, for many years Kirk Sessions had responsibility for maintaining the poor of their parish. As well as administering financial support – often referred to as outdoor relief, in the sense of providing support outwith a poorhouse – some sessions also maintained records of visitations. These involved representatives of the Kirk Session periodically visiting the poor of the parish. Not many of these records survive, but where they do, they can be extremely interesting.

One parish where they do survive is Scone, in Perthshire. Included at the end of the Parochial Board letter book are a series of Notes on visits to the poor. There are 93 entries, so we thought we'd index them.

One entry – or rather series of entries – in particular, caught our attention. The entries start in 1846:

Isabella Whitelaw’s children, Lethendy Moar

Isabella Whitelaw had been arrested and brought before the Police Court, as reported on 23 April 1846 in the Northern Warder and General Advertiser for the Counties of Fife, Perth and Forfar:

Janet Gall or Cochrane, and Isabella Whitelaw, charged with several separate acts of theft some of which were committed beyond the bounds of Police, were handed over to the Sheriff.

Her conviction was reported a few months later:

Sheriff Court

All seemingly goes quiet for the Whitelaw children for a couple of years, but then we find some more entries in the poor visitations:

Isabella Whitelaw’s two children

This time, Isabella’s conviction is reported in the Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review

Isabella Whitelaw, Perth, accused of theft – aggravated by previous convictions, was sentenced to seven years’ transportation.

The National Records of Scotland’s 19th century solemn database adds a few more details: that Isabella also went by the name of Helen Panton, that her address was c/o Robert Mills, cadger, Coupar Angus, Perthshire, that she could not write.

We next hear of Isabella as she is transported to Tasmania on board the Aurora, on 22 April 1851. Her arrival in Tasmania is recorded in the Register of Convicts, on 10 August 1851. She is described as a Country Servant, 5 feet 4 inches, age 31, with a ruddy complexion, dark brown hair, brown eyebrows, hazel eyes, and medium facial features. She was a wart on her left arm at the bleeding place. Her conduct record suggests she wasn’t entirely a reformed character. She was charged for being drunk on October 25 1852. On November 2nd, she was sentenced to 6 months hard labour for being absent without leave. On December 3rd 1852 she was “delivered of an illegitimate child (Mary) at the Cascade Factory”. On 2 October 1854 she was sentenced to 12 months hard labour for absconding. 11 August 1855 saw her being sentenced to 3 months hard labour for being drunk on her master’s premises. A few months later, on 5 November, she was sentenced to another 12 months hard labour for absconding when on a pass. Once more, on 29 June 1857, she was sentenced to one month’s hard labour for being out after hours and absconding. Shortly after the birth of her daughter, Isabella was granted permission to marry Michael McDermott on 14 December 1852. We have not however been able to find a record of them actually marrying. Things however do appear to have eventually improved for Isabella, as she was again granted permission to marry on 2 December 1856, to William Way, a freeman. They were married at the All Saints Schoolroom on 23 December 1856. William was a cabinetmaker. We have not found any more records of Isabella Whitelaw, and do not know if she ever returned to Scotland or saw her children again. Isabella Whitelaw's story is an interesting illustration of how one record can lead to another, and can end up telling a fascinating story. In January 1843, the Conservative government under Sir Robert Peel established a Commission of Enquiry to study the Scottish system of poor relief. There had been growing concerns about the effectiveness of poor relief in Scotland, which at the time was in the hands of the Kirk Sessions of the Church of Scotland. A few months after the Commission was set up, the Church of Scotland split in the Disruption, with around 40% of ministers leaving to form the Free Church. This further eroded the position of the Church of Scotland, and made substantive reform inevitable. The earliest record of poor law in Scotland dates back to 1425 (not 1424 as is sometimes incorrectly stated). Those aged between 14 and 70 who were able to earn a living themselves were forbidden from begging, on pain of branding for a first offence and execution for a second offence: Of thygaris nocht to be thollyt Three years later, the king decreed that officials who failed to implement this act would be fined. In 1535, the system was further formalised. Poor relief was only to be granted to individuals in their parish of birth, and the “headmen” of each parish were to award tokens to eligible paupers, thereby introducing the concept of a licensed beggar. People caught begging outside of their parish of birth were subject to the same harsh penalties as before. An Act for punishment of the strong and idle beggars and relief of the poor and impotent was passed in 1579. This established the basic system of poor relief which was to continue for hundreds of years. Sic as makis thame selffis fuilis and ar bairdis or utheris siclike rynnaris about, being apprehendit, salbe put in the kingis waird and yrnis salang as they have ony guidis of thair awin to leif on If they had no means of sustenance, their ears were to be nailed to the tron or any other tree, and they were then to be banished. The penalty for repeat offenders was death. As for able-bodied beggars: all personis being abone the aige of xiiij and within the aige of lxx yeiris that heirefter ar declarit and sett furth be this act and ordour to be vagabundis, strang and ydle beggaris, quhilkis salhappyne at ony tyme heirefter, efter the first day of Januar nixtocum, to be takin wandering and misordering thame selffis contrarie to the effect and meaning of thir presentis salbe apprehendit; and upoun thair apprehensioun be brocht befoir the provest and baillies within burgh, and in every parochyne to landwart befoir him that salbe constitutit justice be the kingis commissioun or be the lordis of regalities within the samyne to this effect, and be thame to be committit in waird in the commoun presoun, stokkis or irnis within thair jurisdictioun, thair to be keipit unlettin to libertie or upoun band or souirtie quhill thai be put to the knawlege of ane assyse, quhilk salbe done within sex dayis thairefter. And gif they happyne to be convict, to be adjuget to be scurget and brunt throw the ear with ane hett yrne So “strong and idle” beggars were to be captured, imprisoned or put in stocks or irons, and brought before a court within 6 days. Upon conviction, they were to be burnt through the ear with a hot iron. The law puts in this caveat: exceptit sum honest and responsall man will, of his charitie, be contentit then presentlie to act him self befoir the juge to tak and keip the offendour in his service for ane haill yeir nixt following, undir the pane of xx libris to the use of the puyr of the toun or parochyne, and to bring the offendour to the heid court of the jurisdictioun at the yeiris end, or then gude pruif of his death, the clerk taking for the said act xij d. onlie. And gif the offendour depart and leif the service within the yeir aganis his will that ressavis him in service, then being apprehendit, he salbe of new presentit to the juge and be him commandit to be scurgit and brunt throw the ear as is befoirsaid; quhilk punishment, being anys ressavit, he sall not suffer the lyk agane for the space of lx dayis thairefter, bot gif at the end of the saidis lx dayis he be found to be fallin agane in his ydill and vagabund trade of lyf, then, being apprehendit of new, he salbe adjuget and suffer the panes of deid as a theif. In other words, the convicted idle beggar would be spared this punishment if someone offered him a job for a year. If he were to leave such employment without his master’s approval, he would be burned through the ear, but if convicted a second time, he would be put to death as a thief. The law then moves on to detail who should be subject to punishment. Not just beggars, per se, but also: all ydle personis ganging about in ony cuntrie of this realme using subtill, crafty and unlauchfull playis, as juglarie fast and lowis, and sic utheris, the idle people calling thame selffis Egyptianis, or ony utheris that fenyeis thame selffis to have knawlege of prophecie, charmeing or utheris abusit sciences, quhairby they persuaid the people that they can tell thair weardis deathis and fortunes and sic uther fantasticall imaginationes So people claiming to use witchcraft, self-styled “Egyptians” (i.e. Gypsies or Romanies), those claiming to have the gift of prophecy, charms, or fotune-telling. Other people to be punished include those with no visible means of support, minstrels, singers and storytellers not officially approved, labourers who have left their masters, those carrying forged begging licences, those claiming to be itinerant scholars, and those claiming to have been shipwrecked without affidavits: utheris nouthir having land nor maister, nor useing ony lauchfull merchandice, craft or occupatioun quhairby they may wyn thair leavingis, and can gif na rekning how they lauchfullie get thair leving, and all menstrallis, sangstaris and tailtellaris not avowit in speciall service be sum of the lordis of parliament or greit barronis or be the heid burrowis and cieties for thair commoun menstralis, all commoun lauboraris, being personis able in body, leving ydillie and fleing laubour, all counterfaittaris of licences to beg, or useing the same knawing thame to be counterfaittit, all vagabund scolaris of the universities of Sanctandrois, Glasgw and Abirdene not licencit be the rectour and deane of facultie of the universitie to ask almous, all schipmene and marinaris allegeing thame selffis to be schipbrokin, without they have sufficient testimoniallis Those hindering the implementation of the law would be subject to the same penalties. Having established the penalties, the Act requires all poor people to return to their parish of birth or habitual residence within 40 days of this act. Parishes were to be responsible for supporting their native-born paupers or those who had been habitually resident there for seven years, and were to draw up rolls of the poor. Aged paupers could be put to work, and punished if they refused. Children of beggars aged between 5 and 14 could be taken into service until the age of 24 for boys or 18 for girls, and could be punished if they absconded. An Act of 1597 on “Strang beggaris, vagaboundis and Egiptians” explicitly transferred responsibility for poor relief to Kirk Sessions. The 1649 Act anent the poore introduced a stent or assessment on the heritors of each parish to pay for poor relief. The 1672 Act for establishing correction-houses for idle beggars and vagabonds ordered the opening of correction-houses for receaving and intertaining of the beggars, vagabonds and idle persones within their burghs, and such as shall be sent to them out of the shires and bounds aftir specified in Edinburgh, Haddington, Duns, Jedburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Glasgow, Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, Ayr, Dumbarton, Rothesay, Paisley, Stirling, Culross, Perth, Montrose, Aberdeen, Inverness, Elgin, Inveraray, St Andrews, Cupar, Kirkcaldy, Dunfermline, Banff, Dundee, Dornoch, Wick and Kirkwall. By the time the Commission of Enquiry was set up, it was clear that provision was inadequate. The Commission’s exhaustive report (nearly 6000 pages in total, including evidence; even the index is 300 pages long!) made a series of recommendations:

in every such Parish as aforesaid in which the Funds requisite for the Relief of the Poor shall be provided without Assessment the Parochial Board shall consist of the Persons who, if this Act had not been passed, would have been entitled to administer the Laws for the Relief of the Poor in such Parish; and in every such Parish as aforesaid in which it shall have been resolved, as herein-after provided, to raise the Funds requisite for the Relief of the Poor by Assessment, the Parochial Board shall consist of the Owners of Lands and Heritages of the yearly Value of Twenty Pounds and upwards, and of the Provost and Bailies of any Royal Burgh, if any, in such Parish, and of the Kirk Session of such Parish, and of such Number of elected Members, to be elected in manner after mentioned, as shall be fixed by the Board of Supervision This meant that where a mandatory assessment was used to raise funds for poor relief, the Kirk Session no longer controlled the system, although it was still entitled to appoint up to six members of the Parochial Board. When the Act entered into force, 230 of 880 parishes were subject to statutory assessment. Within a year, that almost doubled to 448 (compared to 432 using voluntary contributions). By 1853, 680 parishes were using statutory assessments, compared to just 202 relying on voluntary contributions. The number of parishes relying on voluntary contributions continued to decline steadily, with only 108 doing so in 1865, and just 51 by 1890.

For genealogists, the implications are clear: after 1845, records of the poor will mostly be found among local government records, mostly held in local council archives around the country. That said, there are significant post-1845 poor records found among the Kirk Session records, not least because as we have seen, in many cases responsibility for poor relief remained with Kirk Sessions long after the Poor Law was enacted. However, the records of the Board of Supervision, being a national body, are held at the National Records of Scotland. One of the responsibilities of the Board of Supervision was to hear appeals against inadequate relief. These appeals are an excellent source for family history – they will tell you much about the individuals, as well as their families. They often include medical reports, information on the earnings of applicants and their families, names and details of children and the like. Before 1845, records of poor relief are more often with Kirk Session records. We saw in a previous post how it was possible to trace individual paupers in for instance Kirk Session accounts and other church records. Some of these records can provide excellent detail - we've seen examples of church poor relief records giving names, relationships, occupations, details of payment in kind, poor children being lodged out with other families and so on. They can be therefore be an excellent source for family historians, and should not be neglected. We are currently working on a national index to a particular set of Poor Law records from 1845 to 1894, which we plan to release later this year. |

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed