|

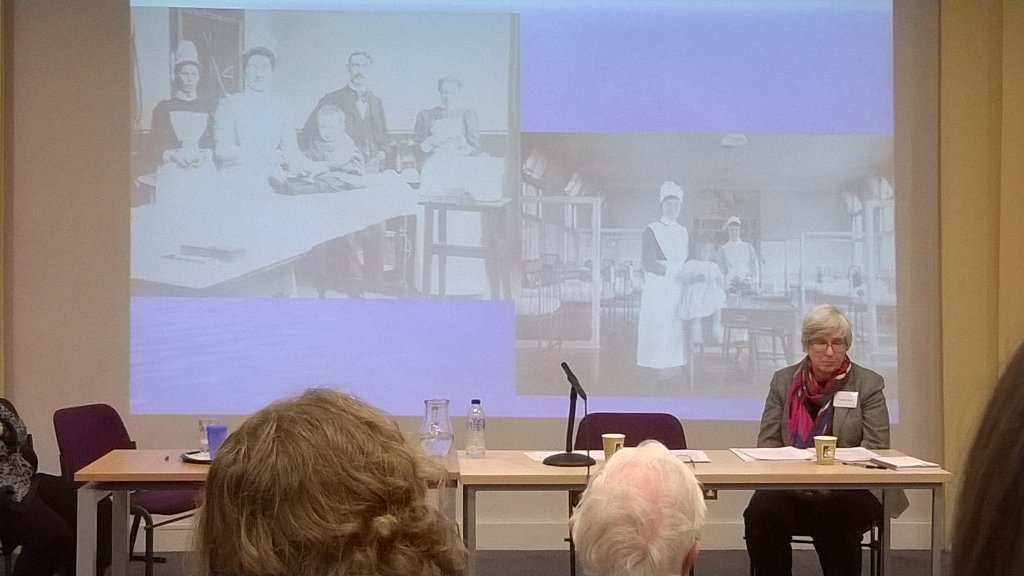

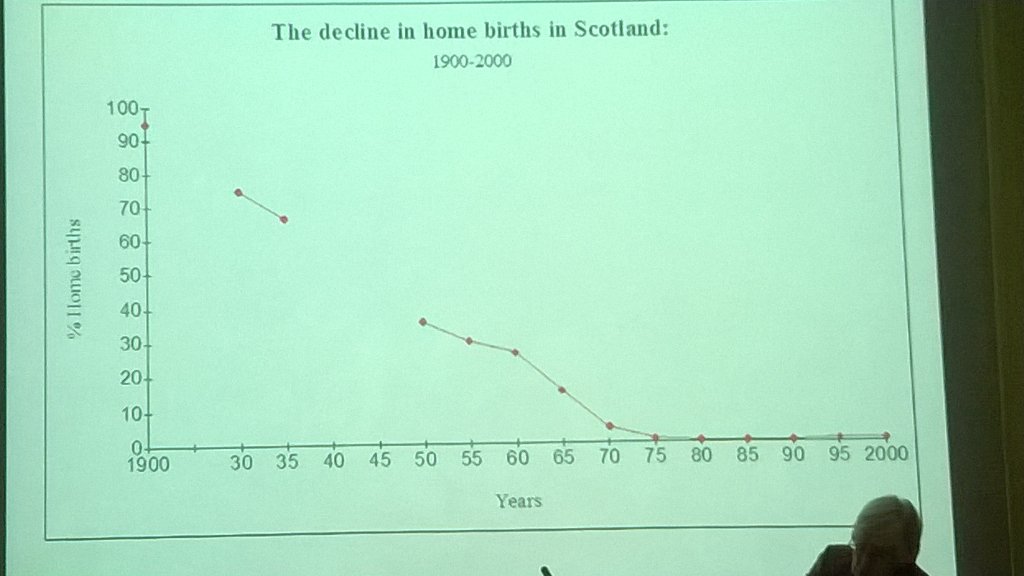

The Scottish Records Association (SRA) held its annual conference in the Soutar Theatre in Perth on Friday on the theme of Public Healthcare Before the NHS. The ten speakers covered a wide range of topics, although they complemented each other, providing a comprehensive overview of public healthcare before the formation of the NHS after WWII. The conference was ably chaired by Professor Marguerite Dupree, of the Centre for the History of Medicine, University of Glasgow, who introduced the speakers and fielded questions from the floor (as well as posing a few of her own). The first speaker was Dr Deborah Brunton, from The Open University, who gave an interesting introduction to the history of healthcare in Scotland. She argued that pre-NHS healthcare in Scotland had acquired a bad reputation that was not fully merited. Although coverage was often patchy (the word of the day, as it turned out), an important principle was established which is arguably the founding principle of the NHS – that a range of quality healthcare should be available to those unable to pay. The charitable hospitals founded across Scotland in the 19th century and earlier offered a reasonable standard of care – by contemporary standards – to their poor patients. The 1845 Poor Law (Scotland) Act established the expectation, if not always the reality, that parishes should provide healthcare to poor people. Dr Brunton cited several examples of public health campaigns in the 1800s: an outbreak of “fever” (probably typhus) in Edinburgh in 1817 led to the cleaning and fumigation of hundreds of houses in the Old Town; and at the height of the 1832 epidemic of cholera, 900 quarts of soup a day was provided free to poor people in Perth. Indeed soup kitchens were established in many towns across Scotland. Dr Brunton was followed by Emeritus Professor John Stewart of Glasgow Caledonian University, who spoke about the provision of health care under the Scottish poor law in late 19th century central Scotland. As Dr Brunton pointed out, the 1845 Poor Law (Scotland) Act required local authorities to provide medical relief. Local medical officers were often under considerable pressure to grant medical relief, even if it was not strictly required. One of the difficulties in studying this period is that the survival of poor law records is patchy (that word again). That said, medical relief spending grew more than tenfold between 1846 and 1900, although the social stigma associated with applying for medical relief meant that some people applied for support too late. Medical care was also often dependent on cooperation between local authorities and voluntary organisations, which was not always forthcoming. Furthermore, there was also tension between the local authorities and the local heritors, who were liable for funding relief – this was particularly the case in rural parishes where there may have only been a few landowners to provide funding. The last paper of the morning session was presented by Sarah Bromage of the University of Stirling and Alison Scott, from Glasgow Life. They described the archives of the Royal Scottish National Hospital (RSNH), held by the University of Stirling. The RSNH was established in 1863 in Larbert to care for children with learning disabilities. As its name suggests, it took in patients from all over Scotland. One of the most interesting parts of the archive is the applications for admission, of which 3014 survive from 1865 to the 1940s. Most of the early applications include plentiful information on the applicant’s family’s circumstances as well as the child’s health, behavioural and educational abilities. Another unusual part of the collection consists of some letters written by the children themselves. More information on the archive can be found here and here. After a short break for coffee (and industrial quantities of fine cake), the next speaker was Dr Jenny Cronin, who discussed convalescent institutions with particular emphasis on the Schaw Convalescent Home at Bearsden. The movement to establish convalescent homes in Scotland began in 1860, in part as a means of easing the problem known in modern terms as “bed blocking”. They expanded considerably – from around 4,000 admissions in 1871 to over 33,000 in 1934. Intriguingly, the Schaw home in Bearsden had a smoking room for men, but a basement work room for women! Dr Iain Hutchison, University of Glasgow, then described the records of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, which he’d studied as part of a four year research project. The minute books record – in a sanitised form – the infighting that sometimes arose in charitable endeavours. Dr Hutchison supplemented the sometimes patchy surviving records with fascinating oral histories, which provided unofficial perspectives on nursing training – one nurse said that the officials “hated us having fun, but we did so anyway”. It took nearly 20 years from the idea being first raised before a children’s hospital was finally established, and it expanded rapidly – from around 500 patients a year in the early 1880s to 10,000 in 1888. Surviving records include Minute books (1861-1948), Annual Reports (1883-1947), Admission Registers (1893-1929), Patient Casenotes (1883-1914), Nursing Records (1882-1948), Records of the Yorkhill Nursing League, and photographs. Interestingly there are not many photographs of doctors, but there are plenty of photos of nurses and patients. The first talk after lunch was given by Ross McGregor, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (RCPSG) on William Macewen, a Glasgow Police Surgeon of the 1870s. As a police surgeon, Macewen was called out to a very wide range of cases, and he was a pioneer in a variety of surgical techniques, often going against established practices. He later went on to establish the Erskine Hospital. McGregor described cases ranging from high-profile murders to rotten fish, and described Macewen’s papers which are held by the RCPSG, the University of Glasgow Archives and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Archives. Macewen was clearly an interesting character – an article he wrote on a case of opium poisoning – a common occurrence – included a quotation of French poetry. Next up was Fiona Bourne, from the Royal College of Nursing Archives, who described the history of the Royal College of Nursing and its celebrations to mark its centenary in 2015. The RCN library is based in London, but the archives are held in Edinburgh. The RCN has always had a dual role, as a training institution and as a trade union for nurses, and has expanded enormously over the last 100 years. I was particularly taken by the lego nurse they built as part of their centenary exhibition! They had a very well received audience engagement plan as part of the centenary celebrations, and learned a great deal about the history of the RCN in the process. The last talk of the first afternoon session was given by Dr Lindsey Reid, on midwifery, and specifically the circumstances surrounding the 1915 Midwives (Scotland) Act. Before the 1915 Act, midwives in Scotland – commonly known as howdies, a term that seems to have arisen in Edinburgh – were entirely unregulated, and often lacking in training. Before then, many howdies didn’t recognise a thermometer when shown one! One possible consequence of the 1915 Act was the steep decline in home births – from 95% in 1900 to only a tiny percentage in modern times. After 1915, unqualified midwives were allowed to continue practising, but were supposed to be accompanied by doctors, although this was not always followed, particularly it seems in the Hebrides, where there was a particularly high rate of “emergency” births – perhaps because the howdies wanted to make sure they got paid! The final talk of the conference was given by Caroline Brown of the University of Dundee, standing in for her colleague Dr Patricia Whatley, who was unfortunately not able to attend. (Caroline did an excellent job – it can’t be easy to give someone else’s talk). This talk was on the Highlands and Islands Medical Service, often considered a precursor to the NHS. The HIMS was established in 1913 following the Dewar report, which examined the poor state of healthcare in the Highlands, where a combination of poverty, distance and dispersed populations made healthcare provision challenging. Highland doctors were often very poorly paid (if at all), and might have to travel for days to see a patient. The HIMS was therefore set up as a public service, with government grants for medical practitioners, district nursing associations to employ nurses, direct employment of doctors and nurses and the provision of support services. Unlike the NHS, it wasn’t free at the point of need for everyone, but its role as a precursor to the NHS is very evident.

Overall – a few very minor technical difficulties aside – this was an excellent conference, and I’d like to thank Kirsteen Mulhern and Robin Urquhart for all their hard work in putting on a great day. I would thoroughly recommend the Scottish Records Association and their conference to anyone interested in Scottish history. I may have even volunteered to speak at next year’s conference as well …

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed