|

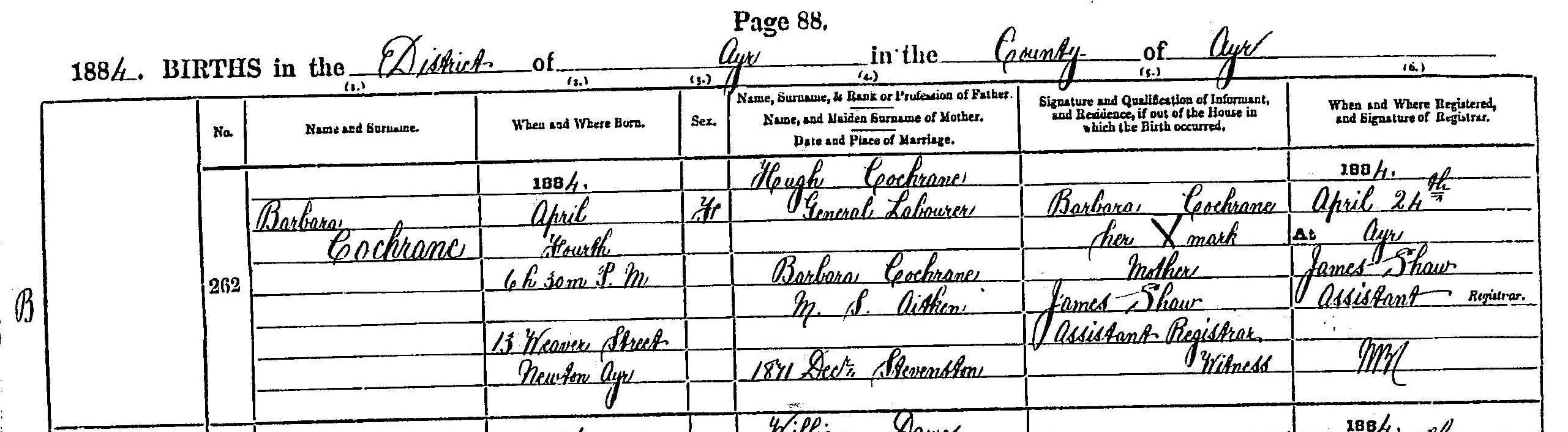

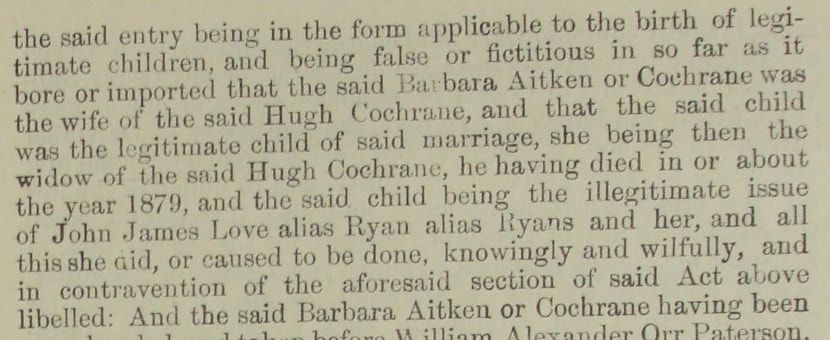

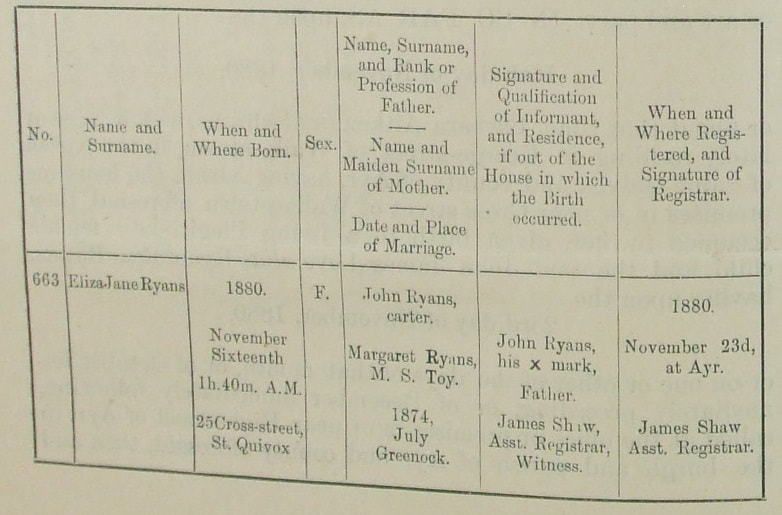

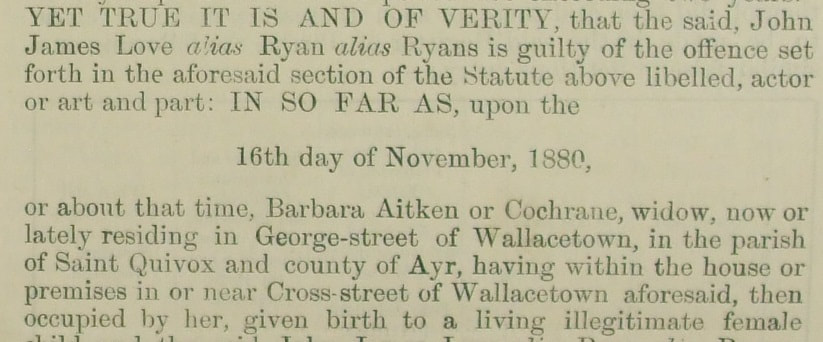

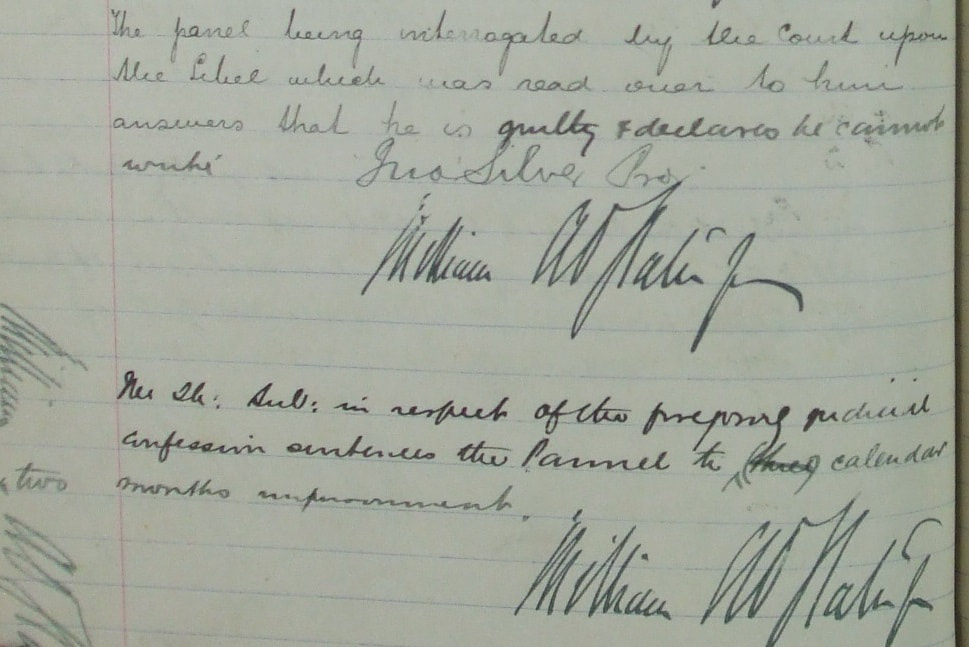

Genealogy is very much about sources – finding them, understanding them, citing them. Not all sources are equal though: a family story, passed down the generations, is still a source, just not necessarily a reliable one. Statutory registers of births, deaths and marriages on the other hand are usually much more reliable, although the accuracy of the information they contain is still dependent on the knowledge of the informant. This is particularly a problem with death registers, as the person providing the information is by definition not the subject of the information, and may not know the correct information. Scotland is unusual, in that it has a system allowing information recorded in statutory registers to be corrected after the event has been registered. This is the Register of Corrected Entries (RCE). One of the most common types of RCE entry is found when a single mother obtains a court order against the father of her child. In such cases, the court (usually a Sheriff Court) issued what was known as a Schedule (F) notification, instructing the registrar to insert in the RCE an entry recording the court’s decree and adding the name of the father to the official record. In theory, there is no time bar on adding to the RCE – the most extreme example we’ve encountered in our research was a birth record being amended more than 60 years later to record a change of name. Statutory registration was introduced in Scotland under the Registration Act of 1854. The government took the accuracy of information contained in statutory registers very seriously. Section 60 of the Registration Act reads: Every Person who shall knowingly and wilfully make or cause to be made, for the Purpose of being inserted in any Register of Birth, Death, or Marriage, any false or fictitious Entry, or any false Statement regarding the Name of any Person mentioned in the Register, or touching all or any of the Particulars by this Act required to be registered, shall be deemed guilty of an Offence, and on Conviction shall be punishable by Transportation for a Period not exceeding Seven Years, or by Imprisonment for a Period not exceeding Two Years. Despite the risk of a prison sentence, people did sometimes continue to lie – about their age, about their family background – and those lies are made official by the act of registration, and might never be corrected in the registers. Fast forward three and a half years, and on 24 April 1884, James Shaw registered the birth of a baby girl, Barbara Cochrane, born on 4 April 1884 at 13 Weaver Street, Newton on Ayr. The informant was the child’s mother, Barbara Cochrane, who informed James Shaw that the child’s father was her husband, Hugh Cochrane, a general labourer. The original register entry gives no indication that anything is amiss. However, on 8 December the following year, the Sheriff Court at Ayr issued a criminal libel against Barbara Aitken or Cochrane, accusing her of contravening Section 60 of the Registration Act, alleging that she had visited the registry office in Ayr and she “knowingly and wilfully” made, or caused to be made “false statements … in order that the said statements … might be entered … in the register of births for the said district of Ayr”. The libel then includes a facsimile of the entry in the Register of Births, and explains how the statements were false: When Barbara appeared in court on 8 December, she pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to one month in prison. Six weeks earlier, on the 27 October, John James Love alias Ryan alias Ryans appeared in court on similar charges. John’s case related to a different child though, one Eliza Jane Ryans: The criminal libel issued by the Sheriff Court, alleged that Eliza Jane was the daughter not of Margaret Toy, but of Barbara Aitken or Cochrane: John pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to two months in prison. Perhaps surprisingly, neither birth record has an associated RCE entry, resulting in a situation where an official record which operates a correction system continues to this day to contain information that the authorities knew to be false. All of this serves as a cautionary tale: genealogists should always treat every source – even those normally considered to be the most authoritative and reliable – with reasonable scepticism - don't always believe what you read. Sources:

2 Comments

Gillian Pidcock

9/8/2022 07:54:46 pm

Just read this blogpost. This is unusual: My g g grandmother Elizabeth Clark was born illegitimate in 1863 and her mother filed a claim against Robert Wedderburn, farmer in Meigle. He appealed twice and lost. In 1987 - 1987? - there was a RCE saying that his name be taken off the record. Why so long after the fact? It's a mystery that I hope to solve.

Reply

Alex Wood

18/7/2024 05:03:57 pm

I'm writing a book on illegitimacy in Scotland and would like to quote elements of the above article ['Don't (always) believe what you read]. Who is the author?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Old ScottishGenealogy and Family History - A mix of our news, curious and intriguing discoveries. Research hints and resources to grow your family tree in Scotland from our team. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Records

- Board of Supervision

- Fathers Found

- Asylum Patients

- Sheriff Court Paternity Decrees

- Sheriff Court Extract Decrees

- School Leaving Certificates

-

Crown Office Cases AD8

>

- AD8 index 1890 01

- AD8 index 1890 02

- AD8 index 1890 03

- AD8 index 1890 04

- AD8 index 1890 05

- AD8 index 1890 06

- AD8 index 1890 07

- AD8 index 1890 08

- AD8 index 1890 09

- AD8 index 1890 10

- AD8 index 1890 11

- AD8 index 1900 1

- AD8 index 1900 2

- AD8 index 1900 3

- AD8 index 1900 4

- AD8 index 1900 5

- AD8 index 1900 6

- AD8 index 1905 1

- AD8 index 1905 2

- AD8 index 1905 3

- AD8 index 1905 4

- AD8 index 1905 5

- AD8 index 1905 6

- AD8 index 1915 1

- AD8 index 1915 2

- Crown Counsel Procedure Books

- Sheriff Court Criminal Records

- Convict criminal records

-

Workmens Compensation Act Records

>

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 2

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 3

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 4

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 5

- Workmens Compensation Act Dundee 6

- Workmens Compensation Act Forfar 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Banff 1

- Workmens Compensation Act Perth 1

- Registers of Deeds

- General Register of the Poor

- Registers of Sudden Deaths

- Anatomy Registers

-

Resources

- Blog

- Contact

- Shop

|

Data Protection Register Registration Number: ZA018996 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed